Slighted by an indifferent world, the utopian visionary Charles Fourier (1772-1837) was not a man for undue modesty. Comparing himself to Newton and Columbus, he set out to discover the ideal principles for bringing order and ‘Harmony’ to community life. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, Fourier felt that positive reconstruction on a new basis was necessary after the destruction of the old order.

A true obsessive, Fourier constructed grandiose schemes and precise urban designs based on an elaborate theory of human passions. Fourier’s planned community was conceived as the built expression of a psychological ‘calculus of attraction’ that supposedly underpins all personal and social relations. Extrapolating from twelve basic types of passion, Fourier dubiously arrived at an exact total of 1620 personality types.

This psychological diversity provided the numerical basis for Fourier’s ideal community – or ‘Phalanx’, as he called it. Laid out in a hilly, rural and temperate location, Fourier specified the perfect social mix for ‘Harmony’, including ‘characters regarded as peculiar’, the wellmannered, and a population carefully selected according to gradations of age, wealth and knowledge.

Connectivity, flow and early rises

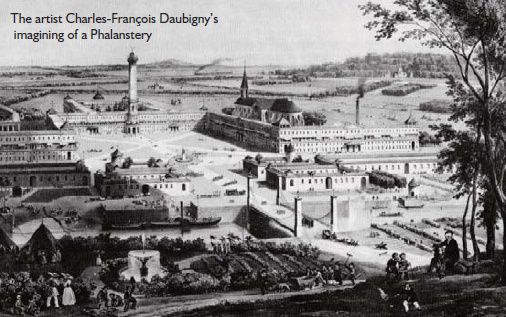

The focal point for Fourier’s utopian community was a hotel-style palace, or ‘Phalanstery’. The central space of the building was designed for quiet study and contemplation. One wing was to be adapted for the noise of industrial work, music and children’s play, while the other wing would contain halls and ballrooms for meeting and socialising with outsiders.

A new architectural style was thought essential to overcome the poverty and stultifying monotony of urban dwelling. The whole Phalanstery and adjacent workshops, halls, and storerooms would be connected by covered passageways, an innovation the great social theorist Walter Benjamin dubbed ‘a city of arcades’. Not for Fourier the Spartan image of utopia, but one with as much opulence as the passions desire. He expected life to be so pleasurable and fulfilling that there would be little time or inclination to sleep past 4.30 in the morning!

The artist Charles-François Daubigny’s

imagining of a Phalanstery

Real-world legacy

Although later identified as a utopian socialist, Fourier defended private property and arranged the Phalanx into three ‘natural’ classes: rich, poor and middle class. His model was that of a joint-stock company, not an egalitarian commune. Despite ’natural’ inequalities of wealth and talent, class conflict would be assuaged by planned spaces, architectural design, universal education, ample and refined cuisine, and group participation in the Phalanx.

In the 1840s, Fourierism became something of a cult movement throughout Europe and America. A number of short-lived Fourierist communities were established in America, perhaps the most notable being Victor Considerant’s doomed utopian experiment in Texas in the 1850s. But instead of bequeathing a wondrous communal palace for us to continue to marvel at, Considerant’s utopia today forms an indistinct suburb of Dallas.

Fourier’s utopianism led to failed communal experiments and bizarre dreams about turning sea water into pink lemonade but it also presented a vision of human communities transforming their conditions of life.