Two pieces of guidance have landed within less than a week, the first from University of Dundee the second from Scottish Government. The former has published the collaboratively produced Understanding the 20 Minute Neighbourhood: Making opportunities for people to live well locally which had a launch event at the V&A Dundee, at which SURF’s Chief Executive joined the panel discussion.

Scottish Government Planning Guidance – Local living and 20 minute neighbourhoods was published on Thursday – perhaps somewhat eclipsed by other Government events – and incorporates case studies that SURF’s People in Place Practice Network has previously platformed.

The University of Dundee guidance has an impressive list of contributors from the sphere of urbanism academics and practitioners and offers reflections on the benefits of the concept and need for public support. It is also clear that it is complex, unique to context and an approach that does not end in a finished end-product – this may be salutary to developers who claim to be delivering a 20-minute neighbourhood in their marketing and planning documents.

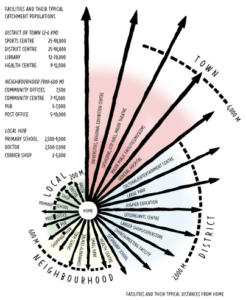

Section 4: Addressing the means to deliver outcomes is strong, particularly on densities, proximity and critical mass which identify quantities necessary to support local facilities. The densest areas of Scotland, such as Leith, are half that of places like Stockholm or a quarter of super dense cities like Paris and Barcelona and the document advocates for medium density, mixed use within urban areas.

Section 4: Addressing the means to deliver outcomes is strong, particularly on densities, proximity and critical mass which identify quantities necessary to support local facilities. The densest areas of Scotland, such as Leith, are half that of places like Stockholm or a quarter of super dense cities like Paris and Barcelona and the document advocates for medium density, mixed use within urban areas.

The page on winning public support has the acknowledgement of the significant role the car currently performs in many lives, both practically and as a sense of identity. Alloy wheels and T-Cut do not substantially improve a car’s performance but do reflect the sense of worth the owner applies to them. Many appreciate that active forms of travel are important to their identity but in the push to have more people travelling actively do not seem to recognise that challenges to car use are felt as an attack on the person, not just their means of transport. Car advertising makes this quite explicit and therefore any ‘war on the car’ is likely to continue to result in an emotive response.

The Scottish Government guidance similarly provides an introductory section on why local living with an overview of the various policy agendas that are encompassed by the 20-minute neighbourhood concept. It introduces a Local Living Framework which aligns with the Place Standard Tool and Palace and Wellbeing Outcomes, providing an approach to thinking about how the concept is delivered and the data that should be gathered.

an overview of the various policy agendas that are encompassed by the 20-minute neighbourhood concept. It introduces a Local Living Framework which aligns with the Place Standard Tool and Palace and Wellbeing Outcomes, providing an approach to thinking about how the concept is delivered and the data that should be gathered.

Both documents require a different application of the concept to rural Scotland with case studies that illustrate its relevance. They also acknowledge the importance of qualitative data and it’s on this that element that the success of the policy stands and most of it is, arguably, outside of the remit of the spatial planning system and transport where it is most commonly discussed. The early presentations to the SURF network revealed that many of the physical aspects needed for local living were to be found in most of urban Scotland: schools, health services, shops and public transport. But subsequent events looked more at quality of provision particularly in our most deprived areas.

Frequency of affordable public transport was commonly found to be wanting as is ability to easily see a GP or dentist. The cost of living crisis has exacerbated the need for affordable food provision and yet the cheapest food is often provided by retailers that work at a scale that is dependent on car driving customers from low density suburbs. More fundamentally the quality of the current maintenance of our existing pavements and the regularity of refuse and litter removal were perceived as barriers to making active travel appealing.

Public attention to the 20-minute neighbourhood concept arises most commonly around alterations to deliver improved streetscape interventions resulting from capital spending ring-fenced for this purpose, while the more basic street cleaning and maintenance goes unaddressed. This may leave local people unimpressed. If your local primary schools and health practices are oversubscribed, then improved public streetscapes will not help. Spending on the one without investing in the other will result in a policy failure.

At the V&A event it was made clear that it required a holistic, collaborative approach across public agencies and local authority services (the Place Principle in action) but my question remains: who is the all seeing eye that makes sure this happens? Maybe part of the answer lies in the Stewarton Case study in the Scottish Government guidance, but it needs resourced and replicated many times. There was also the acknowledgement that it requires long term vision aligned with leadership.

Mixed use, walkable urbanism has been the aspiration of Scottish planning policy for 23 years, the 20-minute neighbourhood is the most recent policy iteration and for it to succeed we perhaps need more honest reflection on why it isn’t already delivered.