SURF is consulting with experts across a wide range of public policy sectors as we develop our 2016 manifesto for community regeneration. In this briefing specially produced for SURF, one of our consultees, Wendy Hearty of NHS Health Scotland, provides a succinct overview of the scale of Scotland’s current health inequalities and suggests eight responses policy-makers could take to address them.

Challenges and Causes

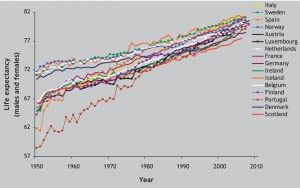

Average (mean) life expectancy in Scotland has improved steadily since 1950, but more slowly than in other wealthy countries.((McCartney G, Walsh D, Whyte B, Collins C. Has Scotland always been the ‘sick man’ of Europe? An observational study from 1855 to 2006. European Journal of Public Health 2011:1-5 (doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr136).))

However, within Scotland the improvement for those living in the least deprived areas, those who are the most educated, and those who are in social class I and II, have seen much faster improvements. Inequalities between them and the rest of the population has grown over the last 35 years.((Leyland A, Dundas R, McLoone P, Boddy F. Inequalities in mortality in Scotland 1981-2001. Glasgow: MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, 2007.))

Inequalities in mortality in Scotland are amongst the highest in western and central Europe, rising rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s.((Popham F, Boyle P. Assessing socio-economic inequalities in mortality and other health outcomes at the Scottish national level. Edinburgh: Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy, 2010.))(( Eikemo T, Mackenbach JP. EURO GBD SE. The potential for reduction of health inequalities in Europe. Final report part 1. Rotterdam: Erasmus MC, 2012.)) This situation is not inevitable and can be improved.((McCartney G. What would be sufficient to reduce health inequalities in Scotland? Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2012.))(( Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Marcelli E, Kennedy M, et al. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960-2002. PLoS Medicine / Public Library of Science 2008;5(2):e46.))(( Thomas B, Dorling D, Davey Smith G. Inequalities in premature mortality in Britain: observational study from 1921 to 2007. BMJ 2010;341:c3639.))

Inequalities are caused by a fundamental inequity in the distribution of money, power and resources. This has an impact on the opportunities for, among other things, good quality work, education and housing. In turn, these determinants shape individual experiences and health throughout life.((Beeston C, McCartney G, Ford J, Wimbush E, Beck S, MacDonald W, et al. Health Inequalities Policy review for the Scottish Ministerial Task Force on Health Inequalities. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland, 2013.))(( Marmot M, Atkinson T, Bell J, Black C, Broadfoot P, Cumberlege J, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review. London: The Marmot Review, 2010.))

The scale of the health inequalities problem is strongly influenced by the magnitude of the underlying inequalities within a society. Action on the worsening trends in health inequalities needs to be re-balanced to address the fundamental drivers of social inequality that determine inequalities in income, employment, education and daily living conditions.

The impact of inequalities on the lives of families and communities was summarised by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission in a 2010 study of the significant inequalities in Scotland. They found that social inequality creates barriers in accessing services and facilities including housing, leisure, transport, justice and healthcare; segregation of children in education between private and public provision; discrimination, social exclusion and lack of participation; targeted violence and domestic abuse; progression in the labour market and workplace discrimination; inequality in access to health resources and advice, and in health outcomes.((Management EaHRCatOfP., 2010, Significant inequalities in Scotland: identifying significant inequalities and priorities for action. Manchester: Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2010.))

The impact of inequalities on the lives of families and communities was summarised by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission in a 2010 study of the significant inequalities in Scotland. They found that social inequality creates barriers in accessing services and facilities including housing, leisure, transport, justice and healthcare; segregation of children in education between private and public provision; discrimination, social exclusion and lack of participation; targeted violence and domestic abuse; progression in the labour market and workplace discrimination; inequality in access to health resources and advice, and in health outcomes.((Management EaHRCatOfP., 2010, Significant inequalities in Scotland: identifying significant inequalities and priorities for action. Manchester: Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2010.))

Eight Potential Policy Responses

1) Introduce a minimum income for healthy living

Reducing inequalities in life circumstances, including income, is one of the guiding principles of effective policies to reduce health inequalities.((Macintyre S. Inequalities in health in Scotland: what are they and what can we do about them? Glasgow: MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit; 2007.)) This includes income arising from both employment and from the tax and benefits systems. Ensuring a healthy standard of living for all is one of the six primary policy objectives outlined in the Marmot Review in 2010.((Marmot M . Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities post-2010. The Marmot Review; 2010.)) The Marmot Review argues that there is a minimum level of income needed to lead a physically and mentally healthy life, and core minimum income definitions do not include health needs.

2) Ensuring the welfare system provides sufficient income for healthy living and reduces stigma for recipients through universal provision in proportion to need

Tax and benefit reforms, including the stricter sanctions regime, increase the risk of persistent child poverty. 180,000 children in Scotland were living in in relative poverty in 2012/13, 30,000 more than in 2011/12. Cribb et al. note that: “both absolute and relative poverty among children and working-age adults look set to increase, in large part due to cuts in benefits and tax credits being implemented as part of the fiscal consolidation. The supposedly binding target of ‘eradicating’ child poverty by 2020 will not be achieved.((Cribb J, Joyce R, Phillips D. Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2013. IFS Report R81. London: IFS; 2013.))

The stricter sanctions regime is also imposing disproportionate social costs. In a 2014 survey of GPs, two-thirds thought their patients’ health had been harmed by reductions to their benefits.((BMJ 2014;349:g4300 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4300 (Published 2 July 2014).)) Research by Citizens Advice Scotland found that the loss of income associated with sanctions meant some clients were struggled to pay for food or energy bills.((Citizens Advice Scotland (2014) Sanctioned: what benefit? A report on how sanctions are operating from the experience of Scottish Citizens Advice Bureaux.)) These problems are compounded by concerns that those who face the most challenging personal circumstances (such as lone parents, people with disabilities, and young people leaving care) are disproportionately more likely to be sanctioned.((Scottish Parliament Welfare Reform Committee 4th Report, 2014 (Session 4) Interim Report on the New Benefit Sanctions Regime: Tough Love or Tough Luck?))

The supply of jobs varies widely across Scottish regions

Welfare policy and practice currently fails to offer appropriate support to help lone parents especially move into work and actively discourages them from investing in training.((Dr Helen Graham, Prof Ronald McQuaid. Impacts of welfare reforms on lone parents moving into work: repor. Glasgow: GCPH; 2014.))

We would suggest that for the strategy to reduce child poverty to be effective, the Government should consider policies that:

- Increase in-work benefits and raise wages;

- Offer flexibility in the rules allowing benefit claimants, especially lone parents, to participate in education while claiming benefits;

- Increase the value of out-of-work benefits and child benefits;

- Create jobs locally where these do not exist;((Taulbut M, McCartney G. The chance to work in Scotland. Glasgow: ScotPHO / NHS Health Scotland; 2013.))

- Invest in high-quality, universal childcare and pre-school education for children aged 0-5.((MacDonald W, Beck S, Scott E. Briefing on child poverty. Evidence for Action, NHS Health Scotland; 2013))

3) More progressive individual and corporate taxation

Reducing inequalities in life circumstances, including income, is one of the guiding principles of effective policies to reduce health inequalities.((Macintyre S. Inequalities in health in Scotland: what are they and what can we do about them? Glasgow: MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit; 2007.)) The Marmot review concluded that tax and benefit structures should be adapted to be fairer, with greater work incentives. Tax and welfare benefit systems are potentially powerful mechanisms for redressing income inequalities. They can also serve as a financial buffer for low-income households, thereby influencing health inequalities.((Marmot M . Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities post-2010. The Marmot Review; 2010.))

4) Active labour market policies to create good jobs – in the right places, of the right kind, offering enough hours and a living wage for parents

Opportunities to work remain very unevenly distributed both spatially and occupationally, especially in South West Scotland and for those looking for employment in elementary and sales occupations.((Martin Taulbut & Mark Robinson (2014): The Chance to Work in Britain: Matching Unemployed People to Vacancies in Good Times and Bad, Regional Studies, DOI: 10.1080/00343404.2014.893058)) There is also a continued shortage of full-time jobs (necessary, though not sufficient, to help families escape poverty). Although the number is rising again, there were 102,000 fewer full-time jobs in Scotland in 2013 compared to 2008.

The minimum wage is also still too low to allow families to meet a minimum income standard (the amount that members of the public think should be covered by a household budget to meet a socially acceptable standard of living ).(( Hirsch D. A Minimum Income Standard for the UK in 2013. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2013.))

5) Develop new housing policies

New housing policies are needed to address availability & affordability problems

Scotland currently faces increasing problems of housing availability and affordability, which affect people living in both public and private sector housing. Rising house prices, lack of access to mortgage finance, high rents, and long waiting lists for social housing, have all contributed towards the housing affordability crisis. Issues of housing affordability span the public and private housing sectors and are most prevalent among low-income groups.

With recent failures in the financial markets and the development of long-term policies, the housing sector in Scotland is changing. There is a decline in home ownership. Because fewer people are able to access social housing, there is an expansion in the private rented sector. Low-income households living in the private sector are more likely to pay higher rents and lack security of tenure. In recent years, the numbers of families living in private rented accommodation has grown. There has also been an increase in homeless applications made to local authorities by private rented tenants.

There is an urgent need to develop housing policies that regulate the private rented sector and support the provision of long-term secure, affordable accommodation for low-income households. Among low-income groups, there is a high demand for social rented housing that is not being met by current housing policies.

The experience of other countries shows that market-led housing policies that promote home ownership as the dominant type of housing tenure do little to alleviate issues of housing affordability. In the current financial climate, fewer low-income households can access home ownership. Intermediate housing products such as rent-to-buy and shared equity schemes cannot deliver the amount of affordable housing needed by low-income households. Therefore there is an urgent need to develop housing policies that support the growth of the social rented sector.((Hands T, Macdonald W, McCartney G – unpublished. A Rapid Review of Housing Availability and Affordability Policy. NHS Health Scotland briefing paper – in production.))

6) Joined up policy and public services to tackle inequalities

At national level, it is vitally important that the responsibility to reduce health inequalities (and inequalities in society generally) lies across government departments. Although the health department retains an important role, all departments have vital contributions to make to ensure that there is a priority given to reducing inequalities across policy areas. The same cross-cutting approach is equally necessary at all levels, including through Community Planning.

Using impact assessments to check that policy development does not inadvertently exacerbate inequalities is a useful approach if they explicitly include such an assessment. There are resources available to support such an assessment.

Where public services are in place, consideration should be given to allocating resources according to need. This will ensure that they do not exacerbate inequalities, and may even make a contribution towards their reduction. This is important in relation to resource allocation between local authorities and health boards, and between areas within local authority and health board regions. It is also important, however, to retain the benefits of a universal system of providing public services in order to maintain the wide public support and efficiency of such systems.((McCartney G, Taulbut M, Scott E, MacDonald W, Burnett D, Fraser A. Response to the Scottish Government’s Expert Working Group on Welfare (EWGW) call for evidence, from NHS Health Scotland. Available at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0044/00441907.pdf, 2013.))

7) Focusing resource allocation on tackling health inequalities

Health inequalities policy should be at the heart of the Government’s drive for social justice, Single Outcome Agreements, and the preventative spend agenda. The priority must be to address upstream fundamental causes of health inequalities that include poverty & income, as well as wider environmental factors such as housing and education, while recognising the downstream consequences like smoking and alcohol abuse.

There needs to be a regular review of policy and resources directed to actions aimed at tackling the fundamental causes of health inequalities, rather than individual lifestyle interventions which do not, on their own, deliver the changes required. Central and local government need to focus on the implementation of the measures that are most likely to be effective, and discontinue those that widen inequalities.

While action will be taken at a national level, a significant contribution needs to take place locally, connecting with communities and raising the aspirations of people that face the biggest challenges. The balance for spending needs to shift away from meeting the cost of dealing with health and social problems after they have developed and towards prevention and early intervention.

8) Advocacy and evidence building

There is an important role for national agencies to support local delivery through advocacy and evidence-building. This includes: building the political will amongst leaders and influencers; expanding and making accessible the evidence base of what works to address health inequalities; spreading effective practice through a workforce that understands the fundamental and wider environmental determinants of health inequalities; raising public awareness and support for effective actions; and ensuring that the voices and experiences of the least advantaged communities are taken fully into account in the planning and delivery processes.