This article is a summary of recently published research carried out by the sustainability consultancy Ramboll on behalf of the Scottish Government and ClimateXChange (Scotland’s centre of expertise connecting climate change research and policy). The study considered the practical implementation of 20 Minute Neighbourhood interventions in Scotland, following a baseline analysis of communities across the country. The article was written by Rebecca Dillon-Robinson, Stefanie O’Gorman (Ramboll) and Anne Marte Bergseng (ClimateXChange)

This article is a summary of recently published research carried out by the sustainability consultancy Ramboll on behalf of the Scottish Government and ClimateXChange (Scotland’s centre of expertise connecting climate change research and policy). The study considered the practical implementation of 20 Minute Neighbourhood interventions in Scotland, following a baseline analysis of communities across the country. The article was written by Rebecca Dillon-Robinson, Stefanie O’Gorman (Ramboll) and Anne Marte Bergseng (ClimateXChange)

Anne Marte Bergseng is Knowledge Exchange Manager for ClimateXChange. She manages research projects on behaviour change and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

Anne Marte Bergseng is Knowledge Exchange Manager for ClimateXChange. She manages research projects on behaviour change and adapting to the impacts of climate change.

Rebecca Dillon-Robinson is an Urban Planner in the Cities and Regeneration Team at Ramboll, based in London. Rebecca works with cities and clients on delivering integrated solutions to tackle major urban challenges including planning for rapid population growth, sustainable development and climate change.

Rebecca Dillon-Robinson is an Urban Planner in the Cities and Regeneration Team at Ramboll, based in London. Rebecca works with cities and clients on delivering integrated solutions to tackle major urban challenges including planning for rapid population growth, sustainable development and climate change.

Stefanie O’Gorman is Director of Sustainable Economics at Ramboll, based in the Edinburgh office. She sits within the Strategic Sustainability Advisory business. Most recently she has focused on the economics of cities and urban settlements with a view to delivering valuable and tangible social and environmental outcomes.

Stefanie O’Gorman is Director of Sustainable Economics at Ramboll, based in the Edinburgh office. She sits within the Strategic Sustainability Advisory business. Most recently she has focused on the economics of cities and urban settlements with a view to delivering valuable and tangible social and environmental outcomes.

We know that 20-minute neighbourhoods are places that are designed so residents can meet their day-to-day needs within a 20 minute walk of their home; through access to safe walking and cycling routes, or by public transport. But can they ever be a reality in Scotland?

A recent baseline study of communities across the country suggests many have the required services and infrastructure to allow them to be 20 minute neighbourhoods. The potential for ‘improvement’ is greatest in some of our most deprived and disconnected places, but it will take a concerted effort across a range of national and local policies and delivery methods to achieve this.

20 minute ambition

The 2020-21 Programme for Government commits the Scottish Government to working with local government and other partners to take forward ambitions for 20 minute neighbourhoods in Scotland. Many communities across the world have made commitments or drawn up plans to support the realisation of the concept. However, only a few have managed to make 20 minute neighbourhoods a reality.

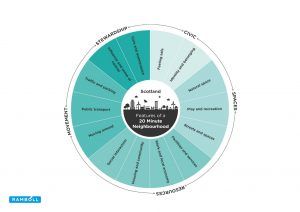

A recent study carried out by the sustainable society consultants Ramboll for ClimateXChange – Scotland’s centre of expertise connecting climate change research and policy – looked at five dimensions that capture the features and infrastructure, and quality of services and experience that make up a 20 minute neighbourhood:

Dimensions of a 20 minute neighbourhood

When looking across all these dimensions there are communities across both rural and urban settings that score well. Some of the obvious examples are affluent areas in our cities, but rural communities are also amongst the high scorers.

However, the assessment does not allow for clear conclusions about the quality of services or infrastructure in a place. Nor has the research looked at whether current infrastructure is actually used for walking and cycling, or if residents use local services or are engaged in local placemaking.

Infrastructure vs performance

One of the examples of a reasonably high-scoring community is Haghill in Glasgow. The area is one of the most deprived in Scotland, yet scores 62% overall on the indicators used to assess whether the community has the infrastructure and features needed to be a 20 min neighbourhood. However, when the data is broken down, there are gaps in service provision, in accessibility and some particularly poor scores for service quality.

In principal, the assessment of Haghill shows the provision of some services in the area, such as access to playgrounds, but issues of severance and quality of place, along with high levels of deprivation, mean that it would likely be very difficult for Haghill to actually perform as a 20 minute neighbourhood. In Haghill many of the shops are located in large ‘out of town’ style shopping centres which are not designed for access on foot or other forms of active travel. With large roads and railway lines severing residential areas from green spaces and services. A clear example of how complex it can be to translate a national level assessment to local conditions. Even when services are located within distances that could make them accessible, the quality of the journey and the built environment make it unlikely that people actually walk or use other forms of active travel to reach them.

Our results show that only in-depth local studies can truly show the nature of what is already available in neighbourhoods – allowing for appropriate targeted interventions.

Developing communities to perform as 20 min neighbourhoods

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to developing 20 minute neighbourhoods. Every place is different, as are the needs of its residents. It is also possible that some of those communities where the ability to engage is lowest, may be where the opportunities to make significant and measurable changes are the greatest.

International examples show that a clear and people-centred plan, developed with stakeholders in the community; residents of all ages, businesses, local charities and groups, and local government, is key to success. In a Scottish context this means that the Place Principle will be a critical tool for successfully delivering ‘complete 20 min neighbourhoods’.

However, it is important to note that, despite good intentions, the concept has the potential to inadvertently or indirectly increase inequalities. There is a real risk that communities who are already engaged can mobilise themselves to access support, including funding and additional interventions, at the expense of other communities less able to engage, for whatever reason.

The concept needs resourcing and delivery at a scale and intensity proportionate to the degree of need. All communities will need some support, but the most in need should have the most support to close the gap.

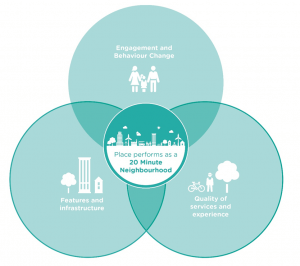

Elements necessary for a performing 20 minute neighbourhood

It is encouraging that the 20 minute neighbourhood approach, as applied internationally, has a significant potential to improve community engagement, and to put in place what communities need on the ground to support behavioural change.

Transport critical to success

20 minute neighbourhoods mean a greater emphasis on reducing private car journeys. A significant barrier to the concept being operationalised is the lack of appropriate active travel infrastructure.

The goal is to make active travel the easiest option for everyone. This can also be an effective way to reduce transport poverty as the cost of transport limits access to services and results in increased social exclusion for deprived communities. While study after study has shown that prioritising active travel, for the most frequent customers, benefits local economic development. It can also have a positive impact on gender inequality as women are less likely than men to have access to a car, yet more likely to ‘trip chain’ multiple destinations.

The aim must be a network of joined up, safe, accessible high quality active travel routes in every town and city. This infrastructure needs to be designed for both transportation and recreation purposes. Routes need to be connected and go where people want to get to, and be delivered alongside high-quality public realm improvements.

Across its dimensions the 20 minute neighbourhood concept provides a mechanism to deliver places which work better for those who live there, provide more opportunity for safe active travel and for local economic activity, and is positive for tackling climate change.

The full report can be read here: https://www.climatexchange.org.uk/research/projects/20-minute-neighbourhoods-in-a-scottish-context/

If you are interested in joining SURF’s 20 Minute Neighbourhood Practice Network you will find more details here.