Spatial planning was a common area of debate in consultations towards SURF’s 2016 Manifesto for Community Regeneration. This was reflected in our final policy recommendations, including better alignment between the spatial and Community Planning systems and doing more to deliver on widely shared aspirations to engage community groups more widely in regeneration, sustainable development and master-planning processes through charrettes and other participative formats.

Since the 2016 election, we have continued to feed SURF network interests into planning policy discussions and developments. Here, we are pleased to publish a joint statement by professional bodies RTPI Scotland, RICS Scotland and ICE Scotland, who have agreed upon five key priorities that they would like to see in a new Planning Bill.

Background

The Scottish Government published a response to the Independent Review of the Scottish Planning System in July 2016, and has since engaged with various sector participants to discuss their response and 10 key actions.

The next step is to publish interim findings in November 2016, with the publication of a Planning White Paper scheduled for December 2016.

ICE, RICS and RTPI professionals in Scotland have local, national and international experience and expertise in planning. All three bodies welcome the Government’s aspiration to further improve Scotland’s already world-class planning system, and share the view that a Planning Bill provides the ideal opportunity to ensure this shared ambition is realised. By working together, we can assist Government in making this Planning Bill effective in unlocking the sector’s potential to drive growth and sustainable development.

Our organisations are not trade bodies; we do not represent any sectional interest, and under the terms of our respective Royal Charters, the advice we offer is always in the public interest as a whole.

With a combined membership of over 21,000 professionals working in planning in the public, private and third sectors, or in vocations that are affected by the planning sector, our organisations are best placed to provide an in-depth assessment of what we, collectively, want to see the Planning Bill achieve.

Roundtable

The three bodies brought to a roundtable its own priorities, with professionals from each organisations discussing and dissecting each priority in a bid to narrow down these priorities to five. Essentially, establishing professional bodies’ wish-list for the Planning Bill.

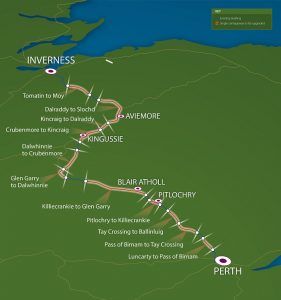

The organisations agreed that whilst the Scottish Government recognises the economic and social benefits from investing in infrastructure, for example the A9/A96 dualling and water quality, they are very much playing catch up due to decades of underinvestment.

The organisations agreed that whilst the Scottish Government recognises the economic and social benefits from investing in infrastructure, for example the A9/A96 dualling and water quality, they are very much playing catch up due to decades of underinvestment.

Furthermore, all infrastructure projects – from the “mega” to the small” – can face a long and unnecessary journey through the planning system. The case example made during the discussion was the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route (AWPR). This took ten years to achieve planning approval – most of which was securing buy-in from challenging local communities.

Conversely, the Government’s announcement of a £3bn investment in social housing is considerable and has been well received. However, whilst this investment may go some way to tackle the chronic housing shortage, it will bring with it the “usual” problems regarding adequate provision of utilities and schools.

Conversely, the Government’s announcement of a £3bn investment in social housing is considerable and has been well received. However, whilst this investment may go some way to tackle the chronic housing shortage, it will bring with it the “usual” problems regarding adequate provision of utilities and schools.

All three organisations were keen to emphasise that as a nation, we need to respect people’s wishes, but also need to push national projects to ensure Scotland’s competitiveness and place in the global market.

There is a need for the Planning Bill to provide answers to how do we solve individuals problems for the benefit of the nation; and how we get balance right of ‘catching up’ and building the next generation of low carbon infrastructure.

There is a need for the Planning Bill to provide answers to how do we solve individuals problems for the benefit of the nation; and how we get balance right of ‘catching up’ and building the next generation of low carbon infrastructure.

Likewise, and in relation to funding to delivery of infrastructure, there needs to be a balance between regional infrastructure fund and developer contributions. The Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) in England has been met with degrees scepticism, but there will be lessons learned which can provide a steer as to how Scotland should take proposals, of a similar ilk to CIL, forward here for delivering infrastructure.

The Five Planning Bill Priorities

-

Infrastructure First

The professional organisations were in agreement with the Scottish Planning Review Panel’s emphasis that there should be “an infrastructure first approach to planning and development”.

The statement argues that major infrastructure projects such as the A9 dualling are a response to decades of underinvestment

The organisations also agreed that the Scottish Government should establish an Infrastructure Commission. This commission, which could bring together utility providers, would have a remit to draw up a coherent, long term infrastructure plan with costed proposals and timelines.

The Commission’s infrastructure plan would be developed in conjunction with community groups, and replace the current Government-developed Infrastructure Investment Plan. This latter document outlines key Governmental projects and programmes, but there is little, if any, detail provided as to why the infrastructure proposals were considered, nor made. Similarly, during the roundtable, the Queensferry Crossing was cited as a major project that attracted top talent to Scotland, but there are few projects, of a similar scale or magnitude that could entice the immigrated talent to remain (once the project is complete) and contribute to Scotland’s infrastructure needs.

The infrastructure first policy, and adjoining Infrastructure Commission, can provide opportunity for Scotland to compete for talent with other European countries. Scotland’s competitiveness in this arena has diminished due to a lack of infrastructure planning – both present and future.

The Infrastructure Commission would take politics out of the infrastructure decisions; ensure that key projects and proposals, which would return the highest economic and social impacts, are given priority; and that there is a constant stream of “choice” projects that could make Scotland a magnet for talent.

-

Resourcing

At present, planning is not resourced sufficiently because it is not regarded as a priority for local or national governments. Indeed, planning is seen as an inhibitor to progress because elected officials shy away from what they perceive as an unpopular decision, instead referring decision making to a Reporter.

Furthermore, Planning Departments across Scotland faced significant cut backs as a result of the recent recession. RTPI Scotland figures indicate that planning department staff in Scotland has reduced by almost 20% since 2010, in addition to a £40m drop in gross expenditure in planning authorities between 2010/11 and 2015/16.

This drop in financial resource can be accounted for by examining how the cost of processing planning applications are not being met by fees – on average only 63% of the costs are covered.

Most developers would be willing to pay an increased planning application fee if there was more certainty in terms of timescales for determining applications, and the ability to engage effectively with Planning Officers at the pre-application stage. The ring-fencing of revenue generated from planning fees for planning departments, particularly for large-scale projects, would be welcomed by the sector.

The Scottish Government must first recognise that resources in the planning system are low and that this needs to be addressed. This will enable discussions around the planning system receiving adequate resources it needs to deliver: finance, staffing, information, intelligence, and systems; be organised to be fit for purpose and efficient; and have skills required. This, essentially, would be achieved through a Government guarantee that planning departments will be resourced to add value.

The organisations were in agreement that improving planning performance should be a priority of the Planning Bill, but this would require additional, if not the full retention, of planning resources.

The planning sector is also failing to attract young talent to the profession, with an evidenced reduction in graduate planners, and private companies experiencing difficulties in recruitment. This needs to be considered and addressed as part of the Planning Bill evidence gathering process.

There was also a suggestion for shared services between Local Authorities. At present, local authorities cannot deliver all functions adequately e.g. ability to competently scrutinise a development viability submission. This notion, however, does require further scrutiny to deduce how best this practice could be implemented.

-

Plan-led approach

Last minute objections from communities tend to be the main cause for the slowing of the planning process. To counter this, a plan-led approach to the process – reversing the more commonly experienced “planning by application” – is required.

Charrettes, such as this one managed by SURF in Rothesay, support a more proactive planning system

Planning proposals requires longer timescales, with ongoing review, which should enable significantly more community engagement. The opportunity to review should allow councils to make amends without resulting in a significant overhaul of the plan.

This will result in a truly plan-led approach that promotes the primacy of the Development Plan through upstreamed community and stakeholder engagement. This should build consensus, provide clarity on responsibilities for delivery, and ensure a smoother planning process. Essentially, the planning process should be more proactive and frontloaded.

The use of charrettes provide ample opportunities for communities and key delivery stakeholders, for example agencies and energy companies, to work together in a plan-led approach.

-

Holistic approach

Historically, different areas of economic and social infrastructure have been treated in silos, with the needs and requirements of each being considered individually.

The organisations believe that the various entities that make up “infrastructure” are, in fact, interdependent systems. The planning, design, construction and operation of each impacts upon the others.

As such, the organisations believe that the Planning Bill should promote collaborative planning across sectors that will allow the system to deliver with efficiency, resilience and ensure better outcomes for end users. In short, by taking an holistic approach.

Additionally, viewing planning with more of a corporate and collaborative function within local authorities and Scottish Government could allow the sector to influence policy and resource allocation. This could provide a degree of certainty of funding for Planning Departments. Constantly changing budgets makes planning for planning far more complex. Consistent, or guaranteed, levels of funding for planning departments, negotiated in corporate engagements, would result in maximised benefits for people and places.

This approach would fit in well with the longer timescales for planning proposals as outlined under the Plan-Led Approach priority

-

Filling the Implementation gap

There is a need to address the implementation gap that currently exists between process and delivery, which the organisations believe can be implemented through careful development of the Planning Bill’s provisions.

The case example used during the roundtable illustrated a Perthshire development proposal of 30,000 homes over 30-40 year period. This build rate of 100-120 homes per year is far too slow; it will not address housing shortage and serves to add pressure to existing “soft” and “hard” infrastructure. For example, 100 new homes built in one year, would not warrant a new school; but the young people in those new homes would still require a place in the existing local school. It would not be until there is a quantum reached that the council would consider building a new school to cater for the 30,000 home development. The same can be said for local transport provision and amenities.

The planning system needs to allow challenges from, both the market and community, but not to the detriment of progress. The timeline of development plans have shifted from five years to ten years, but these plans have to allow for flexibility in order to ensure unnecessary blockages are unclogged at an early stage. One suggested approach was a biennial assessment report of a development plan. This would provide clarity, and ensure plans are still on track and relevant. Built in flexibility would also allow incoming (newly-elected) councils to debate potential changes.

By filling the implementation gap, end users can be assured that the system will provide predictability and enable action. This can be achieved by the system being both delivery and outcome focused.

Concluding remarks

This report was developed through close collaboration between ICE, RICS and RTPI, and has a primary objective to inform Scottish Government ministers and Holyrood parliamentarians of what the Planning Bill should comprise from an apolitical and balanced outlook.

Our organisations have been working with the Scottish Government and parliamentarians on the Planning Bill through their own means, such as individual meetings and the Government-led workshops, and we will continue to make representations in our own right.

All three organisations would welcome the opportunity to continue to engage with Scottish political leaders on the preparation of the Planning Bill.

For further information on this joint statement, please contact the following representatives:

- Sara Thiam, Director, ICE Scotland: sara.thiam@ice.org.uk

- Gail Hunter, Scotland Director, RICS: ghunter@rics.org

- Craig McLaren, Director, RTPI Scotland: craig.mclaren@rtpi.org.uk