The “payment for results” Work Programme employment initiative, introduced by the UK Government three years ago, are facing increasing levels of scrutiny. In this special in-depth article, employability expert and long-standing SURF Director Alistair Grimes (pictured) considers the thinking behind its approach towards reducing long-term unemployment. He also identifies three major flaws that need to be addressed in the next version of the programme.

The “payment for results” Work Programme employment initiative, introduced by the UK Government three years ago, are facing increasing levels of scrutiny. In this special in-depth article, employability expert and long-standing SURF Director Alistair Grimes (pictured) considers the thinking behind its approach towards reducing long-term unemployment. He also identifies three major flaws that need to be addressed in the next version of the programme.

There is currently a flurry of activity as various think tanks, providers and political advisors start to think about the future status and direction of the Government’s welfare to work provision and, in particular, the Work Programme (WP). Depending on the outcome of the election, re-contracting or a new programme will be arriving shortly.

How did we get here?

It might be worth trying to look at some of the thinking behind the WP and what is needed to reduce unemployment before reason and common sense are obliterated by a volley of political point scoring in the lead up to that election.

The Work Programme was launched by the Department for Work & Pensions in 2011.

If we go back to David (now Lord) Freud and his report to the last Labour Government on welfare programmes, which resulted in the Flexible New Deal (FND), we find the themes that have been brought forward into the WP. It is important (I suggest) to remember that Freud moved from being a Labour advisor to a Conservative Minister without any real shift in his views. Whatever the feisty rhetoric across the political divide, both Government and opposition share the same view of the problem and the solution.

Labour feels it must be seen to be tough on benefits and this has boxed it into a position of competing with George Osborne on who can demonstrate the toughest love. It goes without saying that this is a competition it cannot win and has the disastrous side effect of treating unemployed people as if they are the problem, rather than being part of the solution to economic prosperity. Both the Government and Labour are like the captain of a ship in a storm, vying to see how many of the crew they can throw overboard, rather than seeing the crew as the very people who are likely to get them out of trouble through their efforts.

In this Dutch auction we are seeing an emphasis on cost savings rather than value for money. Both parties agree that benefits should be increasingly made as uncomfortable as possible for recipients in order to drive them off those benefits (result!) or into work (even if that work is low paid or part-time), but neither will invest in the quality of provision required to get people who have been out of the labour market for a long time, and who may well have other difficulties, back into sustainable employment. This is partly due to their subservience to Treasury orthodoxy, which isn’t convinced by expenditure on welfare to work programmes anyway and doesn’t buy in to the ‘invest to save’ agenda on welfare. In this view, most expenditure results in either deadweight (it would have happened anyway) or displacement.

Supermarket

Freud’s original view was that a more effective market needed to be created, partly by bringing in private sector providers who understood incentives and innovation better than their public sector counterparts. This would also have the benefit of ‘de-risking’ activities for Government (since private companies would take any risks associated with performance) and would not require up-front capital from Government because payment would be results-based. Freud saw a results-based market weeding out poor performers and, because of the investment requirements of large contracts (more efficient that way), a situation where, in the medium term, welfare to work provision would be like supermarket provision in the UK; four or five large chains with 80% of contracts, but managing supply chains of smaller providers at the local level.

I’ve never been entirely convinced by the supermarket analogy, but it is difficult to argue against the principle of payment by results. Indeed one of the things that has been wrong with welfare to work for as long as I can remember is that payment has been for activity (whether training, more qualifications, life skills or whatever) and that there hasn’t been enough emphasis on getting people into work, helping them stay in work and then moving up the jobs ladder.

But this simple truth contains a number of practical difficulties. The first difficulty is that it depends, to a large extent, on the health of the labour market – on demand. Welfare to work programmes can’t do that much to change demand and one of the misfortunes of both Flexible New Deal and Work Programme was that they began operating at the start of the worst recession for 100 years. It is also difficult to work out what the actual results have been, since there were bound to be teething problems and, if the measure of success was a job for up to two years, problems with ‘too early to tell syndrome’ (which DWP and some providers have been happy to hide behind). However, the view of experts such as the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion (CESI) is that results have been just about the minimum performance required by DWP. Hardly a resounding performance at any stage for a ‘transformative’ programme.

This is not a surprise and was widely predicted by many industry insiders who knew that the funding under WP was simply inadequate to provide a decent service. Almost all those who won WP contracts have been forced into cost cutting exercises to stem losses, resulting in caseloads for front-line staff of over 200 (or under 10 minutes/week/person).

A messy business

The welfare to work industry bears some responsibility for this mess. Instead of making a case for more funding, it not only agreed to DWP figures, but actually promised discounts of from 7% up to 60%. Since these discounts were not to be delivered until the third year of the contract, providers believed that the upturn would have happened by then and unemployed people would be flying off the supermarket shelves, keeping them profitable.

In short, the finances available to the WP have meant a poorer service for claimants and marginal profits (if any at all) for providers, with the longer-term consequence of no resources to invest in development and improvement. Whether or not Deloitte will succeed in offloading their share of Ingeus, the message is pretty clear: “We thought we could make money and we can’t, so we are off. Thanks for all the fish.”

This lack of performance has also left DWP with a number of problems. Even leaving aside the embarrassment caused by the various fraud allegations against old favourites A4E and (admittedly in different business areas) newcomers G4S and Serco, DWP has to decide what to do about underperformers.

The pre-WP rhetoric was full of references to strong measures to identify, warn, punish and then remove those who failed to come up to standard. However, despite some marginal tinkering around changing caseload volumes (‘market shift’ in the jargon), there has been no real appetite to take decisive action. And providers can see this. They know that once the contract has been awarded, there is virtually no chance that it will be removed because it is far too much hassle to do so and then re-tender. This highlights one of the fundamental weaknesses that needs to be addressed in any future WP – the poor level of procurement and programme management in DWP (and government in general; failing IT project anyone?).

The other piece of rhetoric we may as well mention was the ‘promise’ that this would be a real opportunity for the third sector. Unsurprisingly, this was a promise more honoured in the breach than in the observance with the vast majority of contracts going to the private sector (Ingeus, Working Links, A4E, Avanta and so on). It shows the second fundamental weakness with DWP in this process, its limitations as an effective procurer of services. Rather than actively creating a market and managing it, DWP simply administered a competition for money and then defended the consequences (largely on the grounds that putting a number against a subjective ‘score’ makes it objective).

If anyone cared to analyse the bids and the scores attained they will see two important features: a mechanical scoring system that was far too inflexible and the fact that cost outweighed quality in the final reckoning. This approach has conspired to produce the (surely) unintended consequence that the quality of bid writing is now much better, but the performance of programmes is still the same.

What is to be done?

But we cannot change the past (outside of the former Soviet Union, where the past was always unpredictable). If we focus on the future, what might be done to produce a better programme?

This is not the same as just producing better results. The fact that the economy will almost certainly improve will produce better results come what may and it will be all too easy to do very little and then claim the credit.

No, a better programme would have to look at some of the underlying issues and put some long-term thinking into an area where there has been too much pointless change and uncertainty. Underlying this is the fact that politicians and civil servants are, by nature, intelligent design Creationists rather than Darwinians. By this I mean that a welfare to work programme comes about in the following way. The brightest people are brought into a room, design a programme and start it off. The programme cannot be changed (because ‘moving the goalposts’ is a serious mistake in such circles) and, every five years or so, a change of minister, government or the feeling of failure leads to the programme being washed away by the political equivalent of the Great Flood (or ‘refreshed’ as the jargon has it). At this point the brightest people are brought into a room to create a new programme and the cycle repeats itself. Evidence and small scale, adaptive or evolutionary change, is remarkably absent.

This causes a number of major problems, especially the fact that performance always deteriorates prior to, and immediately after, structural change: so the year before any change and the 18 months afterwards are a nightmare for both new and existing providers, not to mention clients.

It follows from this that the way to improve the WP is not to uproot it and introduce a new programme (probably with very few actual differences). Sadly, it is also in the interests of politicians, civil servants and possibly providers to do exactly this. Politicians want to say they have learnt the lessons of failure and are going to produce substantial improvement. Denouncing the last government has a long, if inglorious, pedigree. Civil servants can bury underperformance (including their own) by saying that lessons have been learnt, we have moved on and things will be different this time. Providers, especially bad providers, can tender for the new programme, safe in the knowledge that their past performance will be ignored (because that would create asymmetry in scoring between them and new entrants). In short, everyone agrees radical change will produce uncertainty, extra costs and reduce performance, but in the short-term, many players have a vested interest in going down this path for reasons of advancement or preservation.

What would make a difference without uprooting everything? And please note that not uprooting everything doesn’t mean we can’t have some fundamental changes. I think that there are at least three areas we need to look at.

You get what you pay for

The first goes back to my point about underfunding. Payment by results makes sense, provided that the payments are realistic (and the results are sensible). At the moment, they are not. My memory is that the WP was expected to produce 40% more outcomes at about half the cost of FND and that WP2 is seen as a chance to reduce costs further.

Now there will be evidence from the WP of costs for different groups. Prices, and therefore incentives, need to go up if, for example, serious engagement with the third sector is an objective of the WP and we really want to do something for those furthest from the labour market.

Risk needs to be reasonable

This links to a second point about risk. Third sector organisations do not participate because of both prices and risk. Cash flow is a nightmare, especially for small providers, as is not having firm volumes from their prime contractor, and this needs to be mitigated. There were a number of absurd restrictions, meant to reduce risk in the last WP round. Turnover was taken as a sign of sustainability and financial credibility (DWP would have loved Enron), as opposed to the strength of the balance sheet. More money up front is part of the solution here, without undermining the payment by results principle.

This could be done in a number of ways, for example by linking payments to identifiable and quantifiable measures that we know are marks of progress towards a job (the Ministry of Justice and ESF Families programme both use these). How much should be invested up front must not allow providers to remain solvent by providing a below average jobs performance and how providers will calculate this is actually understood by a number of people who have been in the industry but have now left it. DWP needs to enlist their insights and knowledge.

Keep learning and adapting

This is not a once and for all calculation. Having been to Australia and seen how welfare to work has evolved over 10-15 years, Professor Dan Finn made the important point that government needs to keep re-regulating in this area, as providers will always seek the most money for the least effort. But, pace our comments earlier; to replace the WP with something else hinders the process of learning and improving regulation.

Manage the market

The third area is around commissioning and procurement. The Australian system is partly based on existing providers not having to retender if they meet a quality threshold. This can be set either in terms of a figure for outcomes (e.g. 45% into sustainable jobs) or by saying that the top 50% of providers will have their contracts rolled over. This clearly gives an incentive to perform.

The obverse of this would be that the bottom 25% or those falling below say, 30% into jobs, automatically lose their contracts and are not allowed to retender for at least one round. The remaining 25% would lose the contract but could retender.

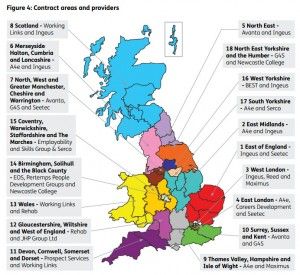

The current Work Programme approach divides the UK into contract area regions, but procurement is largely dealt with centrally.

This would mean both a significant degree of continuity and scope for new entrants, both of which are important. Having everyone retender is expensive and inefficient for both providers and DWP.

This assumes the current system, where DWP divides Great Britain into a series of contract areas and handles procurement at the centre (with some fairly derisory regional input). One alternative, discussed by the Wise Group, is to move to a more devolved set up, in which the Scottish and Welsh governments handle procurement within the devolved administrations and more power is given to English regional institutions. The thinking here is that this is more likely to give scope to medium sized social enterprises with a strong regional footprint, rather than national or international carpetbaggers.

The problem here, as ever, is the English regions, which lack both credible and accountable organisations at that level. Even so, it shouldn’t be impossible to get Local Economic Partnerships together to decide what they need from the WP at a regional level, rather in the way that they have been involved in the recent debate on the next round of EU structural funds. We could start by devolving responsibility in Scotland and Wales (and possibly London) and move to covering the rest of England in the next round of tenders.

Part of the market management issue is defining more clearly the role of the third sector. My own view is that there are some very good third sector organisations in this area and some who are abysmal by any standards. I don’t buy for a second the line that charities and the third sector are automatically better than the private sector (or public agencies) because of their superior values. In short, I don’t believe in rigging the market in favour of the third sector if it cannot perform.

Having said that, it is clearly sensible to keep diversity within a market and to make sure that medium sized third sector organisations can compete on merit and are not excluded by contract size or financial obstacles. This implies, amongst other things, looking at how third sector organisations can fund the investment required and share risks through ‘equity type’ investments, rather than traditional grants and loans.

Finally

Anyone who has been involved in large scale programmes to tackle long-term unemployment will have seen the same mistakes repeated again and again – underfunding, funding the wrong things (activities not outcomes), poor procurement and structural changes in programmes, rather than a focus on the clients needing help and improving performance.

And we need to remind ourselves that unemployed people are not the problem. The overwhelming majority want to work, but need support to get back into the labour market. This requires persistence and continuity as well as high quality provision.