A participant in SURF’s recent Bridging Culture and Regeneration seminar in Dundee, Prof Mark Tewdwr-Jones provided a welcome contribution on the policy and practice context in North-East England. In this feature, he elaborates on the innovative and fruitful ‘Newcastle City Futures’ approach to public engagement in arts, culture, architecture and regeneration.

I live in a city that is often held up as a cause célèbre at successfully implementing culture-led regeneration. Newcastle and Gateshead have embarked on an ambitious programme of physical development along the waterfront of the River Tyne for almost 20 years.

The provision of arts and entertainment venues in the shape of the Baltic Arts Centre and Sage Complex have complemented the ongoing support for places such as the Live Theatre, the Side Photographic Gallery, the transformation of public space along the riverside, the opening of cafes, restaurants and hotels, the bridging of the Tyne with the Millennium ‘blinking eye’ Bridge.

Together, these arts and regeneration initiatives have changed the space that is Newcastle and, in turn, attracted more visitors to the city.

Complexity and Disconnection

But if one dug deeper into the story of cultural regeneration on Tyneside, it is possible to identify much more critical processes at work. These have involved opening up opportunities for public engagement in the city, creating confidence and challenging the working methods of the city council, developers and arts organisations themselves.

As cities become more complex, we often struggle to make sense of change. Recent measures to stimulate economic growth, growing disparities in housing provision in different areas of the country, attempts to install large infrastructure projects in and between places, the introduction of new smarter technology, and rising awareness of environmental costs of extreme weather events, have all created uncertainty not only for politicians and professionals, but also communities too.

At the same time, the ways in which governments and researchers engage and interact with citizens and create dialogues are being stretched or are even viewed as inadequate. Voter turnout in local elections remains low. Members of the public are increasingly turned off by party politics and formal governmental deliberations.

At the same time, the ways in which governments and researchers engage and interact with citizens and create dialogues are being stretched or are even viewed as inadequate. Voter turnout in local elections remains low. Members of the public are increasingly turned off by party politics and formal governmental deliberations.

Traditional public consultation methods are very much on the terms of those initiating the consulting – small timeframes within which society and individuals can express their views on pre-defined policies and proposals. These are often narrowly geographically focused. Even when more innovative participatory approaches are rolled out, there is some scepticism as to whether anything will change as a result of the efforts.

Creating New Urban Dialogues

It was perhaps with this in mind that the Sir Terry Farrell Architectural Review discussed the importance of governments, professionals and others engaging positively with citizens on changes in the built environment. The review report, Our Future in Place, published in May 2014 by the UK Government’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport, laments the current inadequate methods to engage communities on their terms.

Exhibits and artefacts were made available for public viewing

Farrell calls for the establishment of an ‘urban room’ in every town and city as a way of bringing residents into the heart of discussions about change. An urban room, he suggests, would be an exhibition space, a learning space, and a community space, and would explore the past and think about how to plan for the future.

In short, rather than treat regeneration as a physical development task alone, make it an engaging process and use arts and culture as a means of achieving a broader platform to discuss change.

In 2013-14, I was fortunate enough to lead a team that initiated an innovative city-wide participatory method in Newcastle and Gateshead using ideas that Farrell had discussed. The experiment would not form part of the formal planning consultation methods, nor would it be owned by the city council, professional planners, architects or developers.

Rather, it would led by the University and be forged from a partnership of public, private, community, arts and voluntary groups in the city, and combine story telling, imagery, exhibition, and interactive events and be housed in a city centre location neutral to any one organisation. It would be named Newcastle City Futures, financed by Newcastle University but reliant on material, support and goodwill provided by partner organisations.

A Big City Conversation

Originally conceived as a small exhibition celebrating architectural and planning achievements in Newcastle upon Tyne since 1945, the event became a much larger exhibition as a backdrop to a rich programme of events over a three week period.

One evening event discussed the future of the Tyne & Wear Metro

It took place in the Grade I listed Guildhall, located in a prominent location on the Quayside adjacent to the world famous Tyne Bridge. The more historic artefacts on display in the exhibition were intended to act as a prompt to discussions, debates, launches; essentially what the organisers called a ‘big city conversation’, jointly hosted by the University and the University’s partners, which aimed to engage different communities in the city’s change and renewal.

The exhibition was multi-media and comprised: exhibition boards and explanatory stories; historic films; audio tapes of community members; an extensive photographic collection of many unseen pictures of the city; city models showing change and built and unbuilt developments over time; and exhibition stages for future developments. It was structured broadly around three themes: past, present and future.

The focus was on the city, both Newcastle and Gateshead on either side of the River Tyne, rather than the larger Tyneside conurbation. Among the prominent developments discussed were: the planning of housing including the Byker Estate, community life in Shields Road, the conservation of Grainger Town, the redevelopment of St James’ Park, the Central Motorway construction, the transformation of the international airport, the building of the Metro, and the creation of the regenerated Quayside.

Imagination, Innovation and 2400 Individuals

At an early stage, the team decided to make it more than just an exhibition, with the designation of a partners’ space, dubbed the City Forum, within the Guildhall to allow partner organisations to present their plans and strategies for the future of Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead.

This involved constructing a stage area, creating seats for 70 people, and setting up audio-visual equipment where none had existed previously. This gave the initiative much more of a contemporary feel with the platform allowing for the staging of presentations, films and panel debates, on Newcastle past present and future. It enabled audiences to engage directly with experts, officials, community and business leaders on the one hand, but to interact with artists, performers and cultural ambassadors on the other.

The exhibition featured a children’s activity area

The Newcastle City Futures event was officially opened by Professor Sir Peter Hall on 23 May, and ran until 10 June 2014 when it was closed by Nick Forbes, the Leader of Newcastle City Council. Over 19 days, there were 2400 visitors and 24 free events at the Guildhall, linking up 22 different partners across the city.

Newcastle City Futures heard about long term expansion plans for both the Metro and the airport, considered the position of refugees in the city, how to develop an age friendly city, gave opportunities for discussion of economic growth and new architecture in the region, and the long term plan for Science Central.

Asking partners to reveal their plans in innovative public facing talks and presentations that most of them had not experienced before was risky, but they pulled through. Two new films about Newcastle were also screened. There were visits from both school groups and from business leaders who used the space to sell investment opportunities in the city. Children’s activity events centred on drawing, designing and making city models.

It was a resounding success, forging new links between individuals and organisations and paving the way for future discussions about what the city could become.

Studying the Past, Defining the Future

The Discovery Museum curators were delighted with the way the public responded to some of the exhibits that had previously never been exhibited. Amber Collective dusted off some of their iconic photographs and films for public viewing. Representatives of the arts on Tyneside came out of their galleries and centres and engaged with the public face to face.

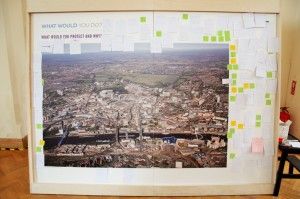

Public comments on an aerial view of Newcastle

The critical mass was achieved by ensuring that the programme was as inclusive and diverse as time and space allowed, and permitted multiple voices to be heard throughout the exhibition, giving smaller organisations and community groups equal footing with large private sector partners. Cultural artefacts of the past were used to tell the story of regeneration and renaissance, and also prompted visitors to think what they wanted to see in the future.

At face value, this appeared to be an exhibition on planning and architecture, and it could be read as such. But for the team it was always viewed as a unique method and process of demonstrating how academics and the university can act as brokers between the public, private, community and voluntary sectors. The civic university is only effective when it has social entrepreneurs that take risks at initiating pioneering attempts to showcase the talents of the academy in ways that have not been achieved before.

At a time when the public have an increasing appetite for engagement in city development and change, Newcastle City Futures demonstrated what is possible in urban areas if one embraced arts and culture in telling the story of regeneration past, present and future.

A short film about Newcastle City Futures is available on YouTube. An extended version of this article was published in the Journal of Town & Country Planning in September 2014