Is constitutional change likely to positively or negatively affect the number and quality of jobs in Scotland? This was a key point of debate for the SURF network in our first regeneration and the referendum event. We have a timely juncture, then, to look back at an earlier post-devolution plan to improve the Scottish economy: the ‘Smart, Successful Scotland’ strategy. Here, Charlie Woods, who played a key role in the plan’s implementation and monitoring via Scottish Enterprise, revisits the thinking behind the approach a decade on.

The ‘refreshed’ Smart, Successful Scotland strategy was launched ten years ago in 2004

The second edition of Smart, Successful Scotland (SSS) was published ten years ago this year (it was a refresh of the first version published in 2001). SSS provided a strategic framework for Scottish Enterprise and Highlands and Islands Enterprise and their networks of local enterprise companies operating across different economic geographies in Scotland.

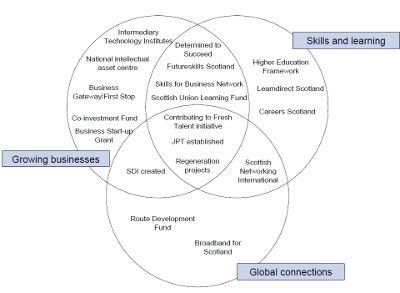

To recap, SSS had three main pillars, each with a number of sub themes:

- Growing Businesses – entrepreneurial culture, businesses of scale, e-business, innovation and research commercialisation, key sectors;

- Learning and Skills – labour market effectiveness, young people, closing the employment gap and reducing economic inactivity, skills for people in work;

- Global Connections – involvement in global markets, globally attractive location for firms and people, connectivity.

The 2004 version of SSS had a much more explicit spatial dimension than its predecessor, with a focus on city regions and rural development, regeneration and strengthening communities. There were also two cross-cutting themes: sustainable development and closing the opportunity gap for people and places. Both versions placed a strong emphasis on the partnerships needed to achieve the strategic goals across the public, private and third sectors.

A measurement framework was also developed for SSS to monitor progress both in absolute terms and relative to other places. Overall measures used were GDP per head and CO2 emissions. There were also a number of subsidiary measures for each of the themes, such as the proportion of employers exporting, graduates as a proportion of the workforce, and the unemployment gap between the worst 10% of areas and the Scottish average. This helped focus investment.

SSS reflected an approach to economic development that was about investing to realise economic potential, with its focus on Scotland’s corporate, human, and physical assets. The overall aim of the approach was to achieve more, better or faster investment than would otherwise take place. SSS reflected a need to use public sector investment to stimulate private investment through a combination of improving the overall economic environment and identifying specific strengths and industries that offered development potential.

Over the latter part of the 20th century, the balance of attention increasingly moved towards realising corporate and human potential, reflecting the changing nature of the economic environment. One side effect of this was that in an increasingly intangible world there was a danger that the contribution of physical assets and the nature of place would be overlooked – the second version of SSS went some way to addressing this with its explicit spatial focus.

Rising income inequality is a growing concern for economic development policy-makers

Economic development strategies are formed against the backdrop of a constantly evolving context, which seems to change ever more rapidly – involving markets, competitors, technology, transport, telecommunications, capital flows, migration, politics, tastes etc. SSS was developed against a background of increasing globalisation, technological advance, deregulation, liberalization and the growth of major new sources of markets and competition. This was reflected in the main pillars of SSS combining business, technology, skills, infrastructure and greater international openness to trade, investment and talent.

There was also an increasing importance attaching to the scale and concentration of economic activity, with the further development of a number of global economic centres attracting investment and talent. In the case of the UK, this was reflected in growing significance of London and its surrounding area on the economic landscape. The viscous and virtuous circles of cumulative causation, first identified by the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal in his 1957 work “Economic Development and Underdeveloped Regions”, now seem stronger than ever. This means that more peripheral areas must try to combine generating as much critical mass as they can in certain niches where they have some advantage, while being as well-connected (physically and virtually) as possible to global centres of activity.

A key challenge for any development strategy is to ensure that the investment made is sustainable over time – that it nurtures a place’s stock of assets, while generating a flow of income to improve wellbeing of the current population. Increased productivity is the key to increasing income while sustaining capital, allowing the consumption of earned income and avoiding the depletion of the capital stock. This requires a broad definition of what constitutes capital and a careful stewarding of each type of capital, be it financial, manufactured, social, human or natural. The attention to productivity growth in general and resource efficiency in particular within SSS reflected this.

In recent years there has been an ever increasing appreciation that inequality has a longer term economic cost, as well as an immediate social cost, in such things as wasted assets, reduced demand, higher public spending and increased financial speculation and associated instability (see, for example, Joseph Stiglitz’s “The Price of Inequality” and Angus Deaton’s “The Great Escape”). The attention paid by SSS to closing employment and activity gaps was a reflection of the need for balanced development to help ensure that as many people as possible benefited from and contributed to economic progress.

The partnership focus of SSS is probably more important than ever. Joined up, coherent investment by the public, private and third sectors is vital if the most is to be made of the potential that exists for sustainable development. Scotland is a relatively small place in a growing world. Making the most of all our assets as efficiently and effectively as possible will be critical for securing development in the short and long term.