The increasing challenge for Scotland’s towns was the subject of a series of short Scotregen articles in 2005.

In the last issue of Scotregen, Roland Hann and Steven Boyne argued for a stronger focus on the regeneration of Scotland’s towns. Here in a summary of their second report, they focus on the context and challenges for the urban landscapes that have played a significant part in Scotland’s industrial and social development.

The former industrial towns

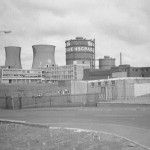

During the19th. and 20th. Centuries, the growth in Coal, steel, textiles and significant changes in agricultural production, created Scotland’s industrial towns and sustained their expansion.

Subsequently, the decline of the industrial economy has contributed to their demise and the challenges they are facing today. However, they are still the places of residence for a significant number of Scotland’s population and often equal or even larger than Scotland’s new cities.

Water, access to raw materials and transport played a key role in their development.

Greenock on the Clyde Estuary, for example depended on the heavy industry while Paisley, further inland, was a major textile industry centre. East of Glasgow we find the Lanarkshire coalfield and steel towns.

A proximity of housing and industry shaped their character and living conditions.

However, today, the industries that supported these towns have largely ceased to exist, new roles to fill the vacuum have not been identified and large gaps have been left.

This situation is reflected in the social situation of these towns and their ‘urban landscapes’.

Educational attainment and unemployment levels reflect the social situation.

As regards levels of education, many of the old industrial towns we examined fall considerably short of the Scottish average – compared to a Scottish average of 33 per cent, in Cowdenbeath, 43 per cent of 16 to 74 year olds have no qualifications or are not in full-time education, while in New Cumnock this figure is even higher at 58 per cent (GROS 2004).Comparing these figures to those for Scotland’s cities, only the old industrial cities of Dundee and Glasgow show the same low levels of educational attainment.

Unemployment in Scotland’s old industrial towns is between 11.9 per cent and 43.1 per cent higher than the Scottish average. With nearly 50 per cent of Scotland’s population living within the towns, the severity of the situation justifies a stronger policy focus.

The impacts on the urban landscape

The decline of the traditional industries and the demolition of industrial buildings has left its scars and often fragmented and disjointed townscapes.

Past and recent attempts to attract inward investment have not managed to fill the gaps and furthermore any business investment has primarily been focused on retailing.

This has increased traffic and the number of shoppers, but due to the lack of varied uses this has not contributed to the development of a new urbanism.

The sociologist Hartmut Haeussermann identifies as the four main characteristics of “urbanism”:

• the presence of a variety of people;

• activities and lifestyles;

• period and time differences in relation to building styles;

• and activities and value differences.

These characteristics can not be planned but have to develop over time.

Although dereliction and its associated negative images deriving from the industrial legacy and declining town centres have been identified as hindering development, new housing developments have, however, largely taken place on greenfield sites with no service and community links.

The situation is similar in connection with business parks. For example, while two new large business parks in Lanarkshire have been developed on greenfield sites, links to the towns in Lanarkshire do however not exist. Owing to their isolation from the surrounding communities, these business parks can be described as enclaves.

Windows of Opportunity

The question arises: where are the windows of opportunities in this spatial scenario for Scotland’s towns and their citizens?

A rethinking of the economic development strategies and a stronger focus on local resources and the towns could provide new opportunities. Attending to local issues has to be compared to the laying of foundations for new developments.

Architecturally, structurally, functionally and socially diversified urban townscapes, provide an environment that is attractive to residents and knowledge-based industries. The functioning of these industries depends upon employees having access to urban facilities that are compatible to their lifestyles and working cycles.

Changing the fortunes of Scotland’s economic development outside the cities  requires a stronger focus on the urban environment and characteristics. We therefore argue that a focus on these elements and the effective use of local resources is essential for sustained development. A refocusing of development activity and investment away from greenfield sites to the core areas of Scotland’s towns is essential if long term social and economic benefits are to be achieved.

requires a stronger focus on the urban environment and characteristics. We therefore argue that a focus on these elements and the effective use of local resources is essential for sustained development. A refocusing of development activity and investment away from greenfield sites to the core areas of Scotland’s towns is essential if long term social and economic benefits are to be achieved.

In our view the above discussion presents a strong case for a refocus of activities and investment towards the core urban areas of Scotland’s former industrial towns to create the complex and differentiated urban settings that enables urban activities and life to flourish.

– Roland Hann and Stephen Boyne.

References:

• GROS (General register Office for Scotland) (2004) Scotland’s Census 2001, at http://www.scrol.gov.uk/scrol/common/home.jsp

• Hartmut Haeussermann, Lebendige Stadt, belebte Stadt oder inszenierte Urbanitaet, in: Foyer III/95, pages 12 – 14

A full version of the above report is available to SURF members at www.scotregen.co.uk.