As SURF noted in its 2016 Manifesto for Community Regeneration, there is a shared aspiration across policy-makers, practitioners and academics to engage civil society more widely in development and master-planning processes. In this feature, Stuart Watson, an architect and urban designer who works for the Scottish Government, tells us about the Place Standard tool and its role in supporting greater community empowerment in place-based regeneration.

For those of you who have not yet come across it, the Place Standard is based around a question set that allows you, as an individual or part a group, to give opinions about a place.

14 Questions, each informed by research as having an important impact on outcomes for communities, cover factors that impact on well-being. Here I’ll explain a little about how application of the Place Standard tool is spreading, how it can connect and empower and how its outputs should help to shape investment decisions.

Instant Impression

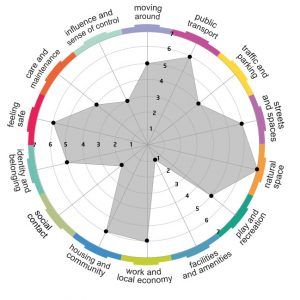

The tool’s scope covers spatial and environmental issues. Questions include the amenities or opportunities that a place offers (including choices on residing or working locally) as well as the social or organisational aspects of place (such as influence over decision-making). After answering the questions, a kind of visual reward is given: a spider diagram. This diagram gives an instant impression of strengths and weaknesses for a place.

This structured framework for wide-ranging discussion helps keep the focus on working out, ‘what are the big issues here?’. But more powerfully, on an everyday level, the Place Standard allows people in a place, whether existing or undergoing change, to have their say. It enables opinions to be expressed, recorded and gathered. Views can then be analysed so that priorities are agreed for the main points to be acted upon.

Since its creation, the Place Standard has proven in practice to manage the tricky balance of making a complex thing, like ‘place’, much simpler to grasp. But it doesn’t oversimplify a score into a headline-grabbing one-liner.

It anchors ‘big thinking’ conversations. Its accessible approach can connect strategic matters of place, that pre-occupy those in leadership roles, very directly with intelligence-gathering from the grassroots – from people who are the community. It establishes a common language for collaboration. Not a bad achievement for a tool only launched in December 2015.

It anchors ‘big thinking’ conversations. Its accessible approach can connect strategic matters of place, that pre-occupy those in leadership roles, very directly with intelligence-gathering from the grassroots – from people who are the community. It establishes a common language for collaboration. Not a bad achievement for a tool only launched in December 2015.

Informing Investments, Tackling Inequalities

The tool is designed to address a simple yet fundamental question

Application of the Place Standard is popular where local government, or a partnership of organisations with responsibility for delivering services, wants to understand how a community feels. To find out what are the underlying issues of the people who inhabit a neighbourhood.

However, planning for investment usually involves public and private sectors. I’m from a built environment design background, so delivering development of quality consisting of that places are more than functional – they can have a positive effect on people’s lives – has always been an aspiration. Therefore momentum in use of the tool so far is heartening, because it begins to join the dots between design, delivery and user satisfaction following a change in public provision or investment of some form.

By re-application, we could find out whether spaces are really perceived as safer, amenities are actually better kept or, an authority is more responsive. The list could be long since the tool’s scope covers complex areas of the public realm – streets, parks, spaces for leisure – places where people want to gather or socialise beyond their front doors. Application at early stages of design thinking should help developers or design team members to consider wider questions: will doing this really help make an attractive place where people want to be?

The tool is proving very relevant in many types of place. Not only where café society already exists – the kind of place where people want to be, be seen and visit – but, importantly, in the many faltering places, urban or rural, where visitors don’t go and where people who can afford to buy homes tend to not choose to live.

This is because the tool doesn’t shy away from the challenging ‘placemaking’ aspects such as: is there access to local work; are there suitable housing choices (for all ages and incomes); and do people think their voice has any influence at all? An essential part of the tool’s implementation plan is to tackle health inequalities.

The Tool in Action

An example of use as part of regeneration consultation processes is in Broomhill, Greenock, outlined within an evaluation report on early use. River Clyde Homes and Inverclyde Council used the Place Standard to engage with the community and to facilitate focus group discussions with residents about place-based priorities. The output identified themes of Facilities and Amenities, Play and Recreation, Natural Space, and Streets and Spaces as priorities.

These findings were shared to inform action planning across relevant services with an agreement to follow up over time using the generated baseline to monitor improvements. Key learning points were that the scale of the place was ideal for this tool and that ease of use made it a good structured engagement method.

A different approach that deployed an online survey was used across the whole of the Shetland archipelago. The Islands’ Council were aware that traditional engagement methods, such as public meetings, often resulted in low turnout. Their method reached 5% of Shetland’s population over the age of 15. There was a spread across locality areas, enabling the data to be broken down for analysis to identify priority actions within each.

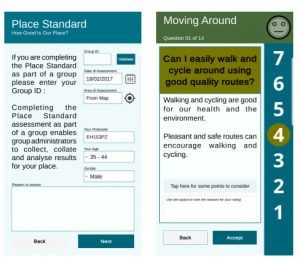

A Place Standard app is now available for Apple & Android smartphones and tablets

However, an issue with both examples was that younger people lacked representation. Due to this gap, common in many early examples, work has progressed to increase the reach of the tool. A crucial part of this has been developing a Place Standard ‘App’, alongside partners in PAS (formerly Planning Aid Scotland).

This app is helping young people to think about the future of their place so fits well with the current planning agenda to involve more young people. The app can be downloaded for Apple or Android devices and is already proving a hit with the teenagers in Galashiels who helped test it in detail. A short film of them using the Place Standard will be published very soon.

The Shetland experience of needing to translate the questions into their own survey method also led to improvements. Using the online tool, group organisers can now collate ratings that are input locally and analyse them within a ‘dashboard’. Results can be exported to sift comments and examine demographic differences such as age-band, gender, specific areas etc.

Because Place Standard assessments are, by definition, all about the local place, then the ability for methodical use of the tool to help align spatial and community planning is already happening in some areas of Scotland. It is also possible to assemble data that can help in making links between location and health inequalities, across the country, in more detail.

The app was tested by schoolchildren in Galashiels (image courtesy of Melt Communications)

We’ve invested to make the Place Standard more accessible, for more use to be made of local outputs, and for good practice to be shared more widely. The potential for success within the regeneration context is only beginning to be realised.

But we know that the tool can take account of feelings and views from the grassroots and link to strategic thinking about place. So it should help shape development or investment that is not only positive from an economic or environmental perspective, but that is really better appreciated by the people directly impacted by it.

To end on a high, the implementation team led by Scottish Government, NHS Health Scotland, and Architecture +Design Scotland received an award this June from RTPI UK for Excellence in Planning for Wellbeing. The RTPI citation said:

“The Place Standard tool is innovative and flexible, and can be applied across the planning system, as well as being accessible to communities. The tool uses a broad definition of well-being which considers everything from buildings and streets to human relationships and social contact. It effectively reveals which aspects of well-being need to be targeted to improve people’s lives…

The tool won a prestigious RTPI UK award in 2017

Responses are translated into an easily understandable graphic which helps to plot the assets of a place. It allows people to work together productively across sectors and boundaries in a consistent way”

The Place Standard Tool has a dedicated website. An evaluation of year one of the Place Standard process, published by NHS Health Scotland, is available here.