Concerns about the ‘suburbanisation of poverty’ have been raised before, notably in relation to cities in the US and England. In this blog, the University of Glasgow’s Nick Bailey and Jon Minton present an analysis of the new Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation data. Their research shows the same trend at work in Scotland’s four largest cities, and explores what this implies about the future for our most urbanised areas – sustainable mixed communities or preserve of the rich?

Successive governments in the UK and the rest of Europe have put forward their visions for “sustainable cities”. They have celebrated the role that urban areas are playing as centres for innovation and drivers of national economies. They have identified the opportunities which cities offer for more environmentally sustainable forms of living. And they have offered a vision of our future cities where different groups live alongside each other without tension in socially mixed communities.

City suburbs like Moredun, Edinburgh, are featuring more prominently among Scotland’s most deprived places

In doing so, these governments are rejecting the previous urban model, marked by deep social divisions, where more affluent groups tended to live in low-density, car-dependent suburbs, while the inner cities were home to above-average levels of poverty.

In the sustainable cities of the future, these visions suggest, higher income groups will be attracted back to more central areas, reducing their need to travel and increasing public transport use – both better for the environment. Importantly, it is claimed that these movements could also contribute to the formation of more mixed communities.

Outer City Poverty

A range of policies have been pursued to try to realise this ‘urban renaissance’. In the UK, these include planning policies which direct housing development towards ‘brownfield’ land in the core of our cities, limiting ‘greenfield’ development at the edge. They also include substantial investment through urban regeneration schemes in land preparation or infrastructure enhancement.

And there is some evidence of success. The population losses which core cities have experienced for decades appear to have halted, and in some cases have begun to reverse. More affluent groups are being attracted back to central areas. But this appears to be happening at the expense of more deprived groups. Low income groups are being pushed out – poverty is ‘suburbanising’. This pattern has been described in the US and, more recently, in England, and particularly London.

And there is some evidence of success. The population losses which core cities have experienced for decades appear to have halted, and in some cases have begun to reverse. More affluent groups are being attracted back to central areas. But this appears to be happening at the expense of more deprived groups. Low income groups are being pushed out – poverty is ‘suburbanising’. This pattern has been described in the US and, more recently, in England, and particularly London.

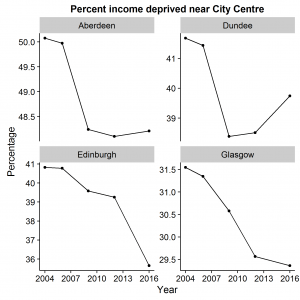

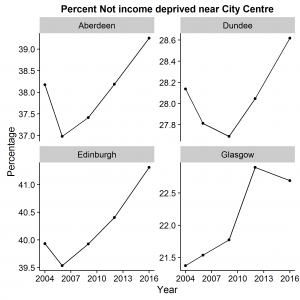

New data released on 31 August by the Scottish Government as part of the Scottish Indices of Multiple Deprivation confirms that the same trend is at work in Scotland’s four largest cities. In all four cities, between 2004 and 2016 the share of each city’s population living near the centre was either stable or rising. But, over the same period the proportion of people in low income households living is areas close to the city centres fell, while the proportion of the non-deprived population living in the same areas rose (Figures 1 ((Fig. 1 Note: ‘Income deprived’ as defined by the Scottish Indices of Multiple Deprivation – essentially people in households in receipt of a low income benefit or tax credit. For Edinburgh and Glasgow, this is the population living within 8km/5 miles of the centre. For the smaller cities of Aberdeen and Dundee, it is the population within 5km/3 miles of the centre. ‘City’ defined as locations with 20km/12 miles of the centre.)) and 2 ((Fig. 2 Note: ‘Income deprived’ as defined by the Scottish Indices of Multiple Deprivation – essentially people in households in receipt of a low income benefit or tax credit. For Edinburgh and Glasgow, this is the population living within 8km/5 miles of the centre. For the smaller cities of Aberdeen and Dundee, it is the population within 5km/3 miles of the centre. ‘City’ defined as locations with 20km/12 miles of the centre.)) below).

In absolute terms, these changes mean that the central area of Glasgow has seen a loss of approximately 6000 people in low income households, while in Edinburgh, the figure is around 4000. For Aberdeen and Dundee, the losses were around 400 and 700 respectively. In all four cases, the non-deprived population in these areas has grown.

A Hidden Process

What is driving this change? Put simply, as city living has become more popular, lower income households are finding it harder to compete for housing in these places. This is a direct consequence of the progressive reduction in housing subsidies available to them, as well as rising levels of inequality more generally. Social housing stock has fallen for decades, meaning more reliance on private renting for those in poverty.

When cities attract wealthier people, higher rents can be charged, and so poorer people have to move elsewhere. Recent welfare reforms have resulted in a succession of cuts to Housing Benefits which subsidise rent payments for those on low incomes. With less financial support, lower income groups are pushed towards lower cost areas, away from the more central neighbourhoods.

The suburbanisation of poverty appears to be a steady but largely hidden process. But it is one which we need to recognise. If it continues, the future for our cities will be far from the visions set out by policy makers and planners. Instead, they will continue to be marked by segregation and deep division, only now with low income households pushed to the edge. That has potentially serious implications for the welfare of these households, and in particular their ability to access employment or services. It also has implications for broader social cohesion in our cities. It does not look like a vision of a sustainable urban future.

Greater detail on the current analysis is available in this report. Earlier work by AQMeN researchers using more limited data had already shown that poverty in Glasgow became more ‘suburbanised’ between 2001 and 2011 – see this briefing.

This work was conducted as part of the ESRC-funded Applied Quantitative Methods Network (AQMeN – www.aqmen.ac.uk)