In October, Edinburgh hosted a major two-day international gathering on participatory budgeting. Organised by the Scottish Community Development Centre and the UK Participatory Budgeting Network, the event explored the progress and impact of PB projects in Scotland and around the world. SURF’s Derek Rankine and Jacqueline Stables were there; their summary of the sessions and workshops they attended follows.

Day One: International Conference

Morning – National context & PB in Paris, Denmark

Over 150 delegates were in attendance at the first day of the conference on Thursday 20 October. It was held in the University of Edinburgh’s John McIntyre Centre, and chaired by the  Scottish Government’s Chief Social Policy Adviser, Prof Carol Tannahill.

Scottish Government’s Chief Social Policy Adviser, Prof Carol Tannahill.

A fitting participatory voting exercise at the start of the day showed that approximately half of the audience were from the third sector, including community groups, with the remainder comprising government officials, elected members, academics, and private sector representatives (the Chair was pleased to note that the latter comprised 10% of the audience). The international element was also in evidence, with a significant number of guests having travelled from England, western Europe, Scandinavia, Africa and North America to take part.

The first keynote speaker was Kevin Stewart MSP, the Scottish Government Minister for Housing and Local Government and former Depute Leader of Aberdeen City Council. Mr Stewart said that he was delighted to be part of a Scottish Government that is keenly promoting participatory budgeting (PB). He claimed that PB is growing in popularity and influence across Scotland, and that its proponents at the highest levels of government are clear that it is not simply a means to deliver useful local activities, but a tool to transform public services, to deliver genuinely inclusive community participation, to reduce health and social inequalities, and to reinvigorate deprived places.

By way of example, he said that Comhairle nan Eilean Siar (Western Isles Council) had successfully delivered a £0.5m public transport PB process, which demonstrated that PB can be about much more than small grant-making for community groups. Mr Stewart also highlighted the Scottish Government’s £2m 2016/17 Community Choices Fund, reporting that grants of up to £100k were awarded to 16 community groups, and also to 12 local authorities for regional PB activity plans. He reported that there were more than 130 applications received, which is another indicator of the still-growing demand for more PB in Scotland.

Pauline Véron, a Deputy to the Mayor of Paris, followed Mr Stewart to provide an international perspective on PB in action. Pauline, whose administrative responsibilities include

Paris Deputy Mayor Pauline Veron elaborated on the city’s PB process

local democracy, youth and employment, elaborated on the remarkable scale of PB delivery across Paris. Tracing its origins back to the city’s historical appetite for revolutions, she noted that PB had been developed in response to a growing concerns around disengagement in local democracy. Paris’ current Mayor, Anne Hidalgo, was elected in May 2014 on the back of a desire to improve the city’s government-citizen relationships, and quickly established a citywide PB process that begin with a €20m pilot programme in late 2014.

The pilot was a big success, so much so that PB is now delivered across all 20 of the city’s arrondissements (districts), with 5% of the city’s budget committed to its continual operation. Residents can develop, share and vote on any kind of project that they feel worthy of public spending. Each citizen has two votes, one for the projects in their arrondisement, and one for major initiatives proposed for the entire city. The turnout is 7-14%, with half of residents voting online and half via ballot boxes. Thousands of projects have been developed and those funded include many that improve Paris’ public spaces, enhance its arts and sports infrastructure, and provide intergenerational social activities. Many of the social projects have helped to support community cohesion between long-term residents and new immigrants arriving from Syria and elsewhere, of which there are more than 100 every day.

Over 150 delegates attended day one of the conference

Conference participants also heard from Carly Colquhoun and Darren Deans from Young Movers for Change, also known as YoMo. Carly and Darren spoke about their experiences with the youth-led charity, which helps young people in north east Glasgow end to improve their confidence, skills and knowledge, such as through supported volunteering opportunities. YoMo runs a successful PB initiative, Glasgow East Youthbank, a genuinely youth-managed project that provides grant awards of up to £500 based on criteria developed by a team of Young Grant Makers.

The morning speakers convened for a short panel session that featured questions on the future of PB. In response to one question regarding the risk of local government indifference, Mr Stewart accepted that there is a mixed picture at present, with some local authorities in Scotland enthusiastically embracing PB and others demonstrating a lack of interest. He felt that this would change soon when more and more decision-makers in local and national government became aware of successful projects as the momentum towards PB in Scotland continued.

One of five morning workshops focused on PB in Denmark. It was facilitated by Morten Ronnenberg and Søren Noes of the Centre for Good Governance and Hedensted Rural Development Board respectively. Participants heard that, in contrast to Scotland, PB does not appear on the national government agenda in Denmark, and only seven of 98 Council

regions are running significant PB initiatives, although increasing numbers are showing interest in the context of its potential for strengthening social networks, especially in places with a disproportionate share of older people and new immigrants.

One of the Danish Council areas with PB in action is Hedensted, a largely rural region in east Jutland with a population of 45k – most current PB interest in Denmark is provincial. Despite the Danish traditions of associations and cooperatives, PB proved to be an initially hard sell in the region, with a number of iterations required to test different approaches towards engagement and democracy and develop a clear methodology. The discussion centred on the difficulties of getting people to understand the concept and generating PB ‘buy in’ from citizens as well as government representatives, and sustaining engagement over the longer-term.

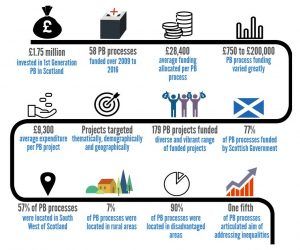

Afternoon – The ‘1st Generation’, PB in Catalonia

In the afternoon session, regular SURF event contributor Dr Oliver Escobar, of the University of Edinburgh and What Works Scotland, presented his new report: Review of 1st Generation Participatory Budgeting in Scotland. Co-authored with Chris Harkins and Katie Moore of the Glasgow Centre for Population Health, the report traced the roots of PB in Scotland to post-dictatorship Brazil in the 1980s. It also identified a “first wave” of 58 PB projects that were carried out in Scotland between 2009 and 2016.

The report’s findings showed that the average funding per PB process was £28,400, with a total investment of £1.75m across the 58 initiatives. Interestingly, 90% of PB processes were located in disadvantaged urban areas, but only 20% of them sought to address health or social inequalities. The national policy drive was also evident in the finding that 77% of the PB processes were directly funded by the Scottish Government. Oliver recommended that the second generation of PB processes should place more emphasis on rural areas, tackling inequalities, digital engagement, and mainstreaming delivery.

The afternoon featured a different set of five workshops, one of which of examined the development of PB in Catalonia, with Gabriel Fernàndez and Joan Cuevas Expósito of Sabadell City Council. Sabadell is Catalonia’s fifth city, with a population of 200k, around 15 miles to the north of Barcelona. The Council developed a PB model in response to the post-2008 recession, which created considerable social and economic consequences, and also high distrust in local government after a series of corruption scandals.

PB conferences in the city of Sabadell, Catalonia

The Council trained nine facilitators to lead PB conferences throughout the city, often in collaboration with charities and independent experts. The PB conferences, which citizens rated an average of 8.1 out of 10, led to the development of a Sabadell Social Strategic Plan that exists to reduce inequalities. The consultations led to higher priority responses to challenges such as food and energy poverty, and alongside Paris provides a further example of PB in action at the heart of city government policy.

In a short closing plenary session, Martin Johnstone of the Church of Scotland and Stephen Gallagher, the Scottish Government’s Deputy Director, considered national ambitions for PB. Stephen reiterated the national policy support for PB and said that its development may be further enhanced in the current Scottish Parliament term by the forthcoming Decentralisation Bill. Prof Tannahill concluded what proved to be a busy, engaging and impressively well-organised day by thanking all participants and speakers for their contributions.

Day Two: Fringe Conference

Throughout Day Two of the Conference, the delegates could select from a host of discussion-based workshops held in three different central Edinburgh venues. Each of the sessions offered an opportunity on how ‘Engage’ in, ‘Think’ about or ‘Do’ Participatory Budgeting (PB).

Small Grant Making process

Community Choices

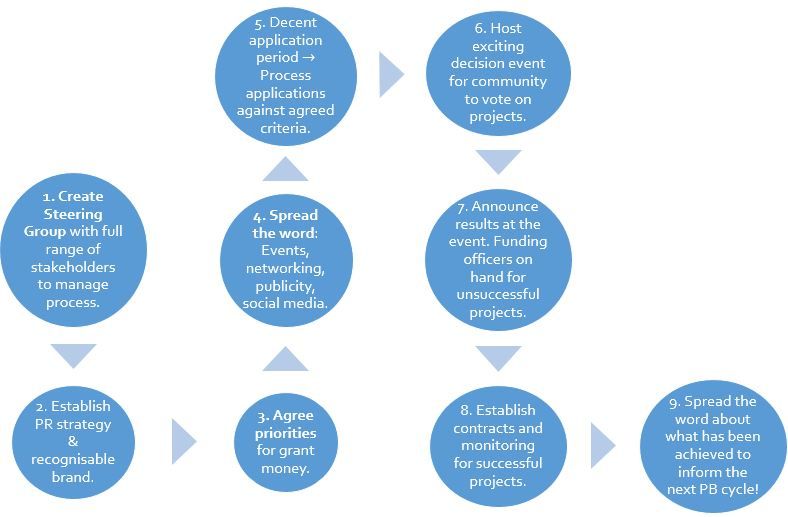

The first ‘Do’ workshop was led by Alan Budge, of PB Partners, who gave a practical guide into Participatory Budgeting (PB) through small grant making (as summarised in flow chart below). This is a process where community organisations apply for small grants from public budgets which are then selected by a community vote at a local event. By bringing together the energy and ideas of community organisations, this process has proven highly successful in building trust in local democracy and greatly improving engagement in local issues.

However, communities may have to persist to acquire political and Council support for this process, as it requires elected members to release some of their decision-making power. To overcome this issue, Budge provided an example from Newcastle where a ‘speed dating’ event took place involving those from public bodies and from the community. This process allowed each party to realise their common interests.

In addition, delegates raised concerns over attracting a representative number of community members to participate in the process. Budge suggested that face-to-face advertising is an important strategy to get individuals involved. Additionally, online voting option can also be used to encourage wider participation, although the ‘decision event’ is still key for community organisations to meet and exchange ideas for future projects.

PB at Scale

Small grant making can scaled up to PB Mainstreaming, as explained by Alan Budge and Sue Ritchie (PB Partners). This involves co-decision making between communities and public bodies on significant mainstream public budgets. Although there is no established method, the speakers provided a range of examples with differing approaches of facilitating PB mainstreaming.

Porto Alegre, a Brazilian city where PB was initiated in 1989, has achieved mainstreaming at a significant scale, involving 50,000 individuals. First, individual communities identify their spending priorities. Next, community elected ‘budget delegates’ are supported to develop these priorities into detailed spending proposals. Based on a community vote, these proposals are then implemented. Overall, $200 million of public spending annually is determined through PB, including construction and services.

However, for those new to PB mainstreaming, it may not be attractive to adopt a full-fledged system immediately. Taking a more gradual approach, the entire Shetlands Council budget has been made available for resident scrutiny and recommendations for any alterations.

On a more ambitious level, the Western Isles adopted ‘community commissioning’ where residents determined the fate of a £500,000 transport budget, specifically to commission bus services. Through careful consideration of the data associated with each of the tender applications, the residents selected a bus company. Perhaps surprisingly for both parties, the Council was highly agreeable with their decision.

Elected Members and PB

As part of the ‘Engage’ series of workshops, Marco Biagi (former Scottish Government Minister and communication consultant) hosted a session to attempt to address the difficulties in engaging elected representatives in PB. This is a crucial element for success as elected representatives must release some of their decision-making power to the community.

In a competitive political environment, Biagi suggested that politicians may engage with PB if they are convinced that it will make them stronger, more electable for the community. Taken a step further, politicians could be challenged to make a manifesto commitment on PB, thereby binding themselves, their colleagues and successors to this participatory process.

On a more basic level, money can be used as the ‘carrot’. For example, Biagi indicated that match-funding and PB support which the Scottish Government committed was an important channel to get local councillors on board, even if they were not entirely convinced by PB.

Once PB is established, a key to its ongoing success is to work with local politicians effectively. This is exemplified by a highly effective PB system supported by the Coalfields Regeneration Trust where they continue to work alongside local councillors.

However, there are still some key issues for achieving support for PB. For example, Local Authorities may perceive a tension between their work and the Scottish Government’s aspirations for PB. Additionally, officers see PB as an inefficient use of time and resources.

The UK and Scottish PB Networks

During a lunchtime session, Sue Ritchie and Jez Hall (UK PB Network) provided a short update on constitutional changes and aspirations for the UK PB Network. The baton was then passed onto the delegates to further discuss these aspirations and to consider the future direction of the organisation. Principally, delegates believed that the Network should have a clearly defined vision. Additionally, based on experience, a representative of the Portuguese PB Network highlighted that it is essential for the Network to act as a political organisation through lobbying.

In addition, there were calls for the Network to spread the word about PB as widely as possible. For those already part of the PB Network, delegates proposed that there should be a focus on capacity building for community organisations, potentially supported by a self-assessment tool.

Developing this conversation further, Paul Nelis (SCDC) led a workshop to discuss the potential for the growing PB network in Scotland. Nationally, PB has become increasingly favoured by policy makers, particularly with respect to the Community Empowerment agenda and the SNP’s manifesto target for 1% of all local government spending to be determined through PB. It is therefore vital to take advantage of this momentum and to determine the direction of the Scottish PB network. Through small group discussion, delegates highlighted that the emphasis should be to widen the Network and support those interesting in starting a PB initiative, through upskilling and confidence building. For established PB initiatives, similarly to the UK Network discussion, there should be a commitment to evolve PB, based on local lessons. In addition, one delegate commented that the Network should developed in a way that advocates full participatory democracy.

Health & Wellbeing

The final engaging ‘Do’ workshop was led by Sue Ritchie and Owen Miller (Mutual Gain) who each have varied, practical experience of utilising PB in a health care setting.

As a step up from small grant making, PB through co-design means actively involving all stakeholders in the decision-making process to ensure the result meets the needs of the users. For example, the speakers highlighted a project where co-design was used to review mental health services. Workshops were held for stakeholders including service users, mental health care professionals and Third Sector Organisations. Interestingly, while the professionals expressed a bias towards psychotherapy, the service users wanted to see greater spending in more short-term Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Although a specific example, the value of involving a range of stakeholders with differing perspectives is clear for making appropriate budget decisions.

As part of the co-design process, the speakers also highlighted a simple, innovative technique of engaging individuals. During three different stakeholder events on reviewing GP budgets, groups were given a notional £1 budget. With this, they could purchase paper cubes which represented the resources available. This proved to be a very effective visual, tangible tool to help the participants understand the viable options when managing a limited budget.

For more on the International PB Conference, please click here to access the event website and official report. In early 2016, SURF published an article on ‘What is participatory budgeting?’ SURF also ran a PB exercise in Gallatown, Kirkcaldy, to deploy resources provided by Creative Scotland, Fife Council and Fife Cultural Trust to local community and arts groups – a report is available here.