Prof. Adams, a key adviser to the Scottish Government’s Land Reform Review Group, has noted that for the last 20 years there has been almost ‘two Dundees’ worth of developable vacant and derelict land in Scotland’s towns and cities. In this article for SURF, he challenges the Scottish Government to adopt a proposed policy mechanism that could prove to be a game-changer for urban land reform in Scotland.

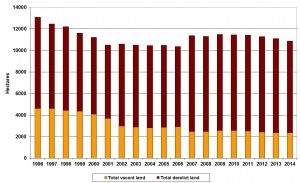

Deindustrialisation left Scotland with an extensive legacy of vacancy and dereliction which continues to haunt its towns and cities. According to Scottish Government statistics (see Figure 1), this legacy has hardly diminished since the late 1990s. Indeed, the total extent of vacancy and dereliction in 2014, at 10,875 hectares, was actually higher than the 2001 figure of 10,517 hectares. Over the same period, urban Scotland has continued to spread outwards, with intense development pressure often experienced at the urban fringe.

Vacant and derelict land in Scotland is geographically concentrated, with 65% of the total found in the six worst affected local authority areas. With the exception of Highland, where two redundant military airfields account for half the total amount of vacant and derelict land, all these areas are located in the Central Belt. They are North Ayrshire and North Lanarkshire (each 12% of Scotland’s total), Glasgow (just under 11% of total), Renfrewshire (just under 9% of total) and Fife (just under 8% of total).

Constraints and Inflated Values

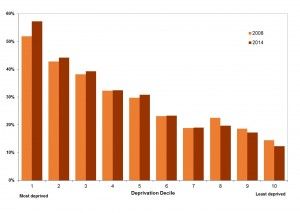

As Figure 2 shows, dereliction disproportionately affects some of the most deprived communities in Scotland and significantly, this has become even worse in recent years.

Figure 2 – % of Scotland’s population living within 500m of derelict land by deprivation decile in 2008 and 2014 (Source – Scottish Govt, 2015)

The overall stock of vacant and derelict land in Scotland disguises limited annual ‘inflows’ of new vacancy and dereliction and ‘outflows’ of vacant and derelict land reused or reclaimed, which reached over 700 hectares each way in the mid-2000s. As far as government action is concerned, however, only 305 hectares of derelict and vacant land was reclaimed or returned to active use between 2005 and 2013 as a result of the £8-10 million spent annually under the Scottish Government’s Vacant and Derelict Land Fund.

Around 42% of all vacant and derelict land in Scotland has been vacant or derelict for at least 23 years. Nearly 75% has probably been vacant or derelict since before 2006. Yet, contrary to popular perception, almost 60% of the vacant and derelict land in Scotland is evidently developable within ten years, and around half of this is considered developable within five years. But, as research has consistently shown, ownership constraints often explain why brownfield land with development potential remains undeveloped over long periods of time. For example, a study of four British cities (Aberdeen, Dundee, Nottingham and Stoke-on-Trent) discovered 146 separate ownership constraints affecting 80 large redevelopment (Adams et al. 2001). These disrupted plans to use, market, develop or purchase 64 of the 80 sites at some point between 1991 and 1995.

Around 42% of all vacant and derelict land in Scotland has been vacant or derelict for at least 23 years. Nearly 75% has probably been vacant or derelict since before 2006. Yet, contrary to popular perception, almost 60% of the vacant and derelict land in Scotland is evidently developable within ten years, and around half of this is considered developable within five years. But, as research has consistently shown, ownership constraints often explain why brownfield land with development potential remains undeveloped over long periods of time. For example, a study of four British cities (Aberdeen, Dundee, Nottingham and Stoke-on-Trent) discovered 146 separate ownership constraints affecting 80 large redevelopment (Adams et al. 2001). These disrupted plans to use, market, develop or purchase 64 of the 80 sites at some point between 1991 and 1995.

The significance of ownership constraints, including unrealistic price expectations, has been widely confirmed by other writers. Almost 40 years ago, for example, Edwards (1977: 206) asked “Why if there is a widespread exodus of capital, with manufacturers and statutory undertakers locating their investments elsewhere, do land values in the inner cities remain so high that the re-use of obsolete land and buildings is impeded?” A decade later, Gloster and Smith (1989: 3) suggested that in the recession of the early 1980s “companies were reluctant to sell at sensible prices, if such prices were below historic cost or book value.”

In 1999, the Urban Task Force south of the border considered that “landowners often have unrealistic expectations of what their site is worth or feel unable to release sites because of the inflated values that are recorded in their accounting books” (p. 223). Most recently, CPRE (2014: 12) argued that “Brownfield site owners are hesitant to sell their land because they speculate that the value may increase in future and as a result brownfield sites within urban areas may remain vacant for a significant amount of time.”

Compulsory Sale

Calling time on vacant and derelict land in Scotland must involve tackling ownership constraints directly. This is why the Land Reform Review Group (LRRG), which reported to the Scottish Government in 2014, recommended the introduction of Compulsory Sale Orders (CSOs) in Scotland.

There are over 10,000 hectares of vacant & derelict land in urban Scotland

These would enable local authorities (and possibly other public agencies and even community groups) to require that land which has been vacant or derelict for an undue period of time be put to public auction. Auctions enable sellers to fulfil any responsibilities they may have to achieve the best possible price and help resolve the inherent difficulties involved in the valuation of abnormal assets such as vacant and derelict land. In policy terms, the immediate and very public sense of market realism engendered by auctions could provide an important stimulus to urban regeneration by ensuring that unused land is made readily available at reasonable prices to whoever can put it to best use.

If the LRRG proposals were to be adopted, any unused site could be subject to a CSO, irrespective of whether it was in public or private ownership, once it had been officially registered as vacant and derelict for more than three years. Owners served with a CSO would then be required to offer the land for sale by public auction within a six to eight month period, with local authorities having reserve powers to act if owners failed to comply.

A CSO would be accompanied by a planning statement prepared by the local authority, explaining what types of development may or may not be allowed in future. This would set out any existing planning permissions and relevant development plan allocations and policies.

Although anyone could participate in the auction, it would be important to discourage speculative purchases by parties who then continued to keep the land vacant. To avoid this, all purchases under a CSO would be subject in law to the implied grant by the new owner to the local authority of the right to purchase the land three years thereafter at a valuation set at that date by the District Valuer if development had not commenced by then. Alongside the planning statement, this would help ensure that bids made at the auction were based on realistic, not speculative, proposals.

If the land remained unsold at auction, a period of time, possibly three years, would have to elapse before another CSO could be served. Such an unproductive outcome would probably be exceptional since, in most circumstances, a community organisation or local authority might be expected to make at least a nominal bid for the land, especially as no reserve price would be allowed. The intended notice period of six to eight months for the auction would also help generate interest and proposals for the future use of the site.

It’s time to call time on urban vacancy and dereliction in Scotland. Not many CSOs might actually be needed to achieve this. But will the Scottish Government begin to take urban land reform as seriously as it does rural land reform?

Professor Adams has produced a series of six policy briefing papers on Scottish urban land reform. These are available on the Policy Scotland website.

REFERENCES

- Adams, D., Disberry, A., Hutchison, N. and Munjoma, T. (2001) Ownership constraints to brownfield redevelopment, Environment and Planning A, 33, 453-477.

- CPRE (2014) Removing Obstacles to Brownfield Development, Campaign to Protect Rural England, London.

- Edwards, M. (1977) Vagaries of the Inner City Land Market, Architects Journal, 165, 206-207.

- Gloster, M. and Smith, N. (1989) Inner Cities – A Shortage of Sites, RICS, London.

- Scottish Government (2015) Scottish Vacant and Derelict Land Survey 2013, Scottish Government, Edinburgh.

- Urban Task Force (1999) Towards an Urban Renaissance, E and F N Spon, London.