Earlier this year, as part of Architecture + Design Scotland’s ‘Glasgow and Venice’ lecture series in The Lighthouse, the Italian academic Nicola Russolo presented his investigation into the relationship between architecture, neighbourhoods, landscape and cultural institutions in the Clyde waterfront area. In this article for SURF, he provides an overview of his research and suggests the ‘bridges’ that could be developed to further maximise the site’s regeneration potential as an interconnected cultural hub.

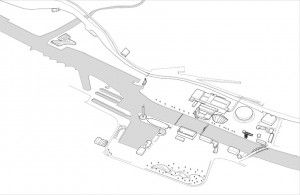

The project emphasised opportunities for enhanced connections between the waterfront area and local parks

No subject would fit better a debate on the theme of Bridging Culture and Regeneration in Glasgow than the Clyde riverfront and its recent development.

The research and design work I’ve done for my Architecture MSc thesis at the IUAV University of Venice, Reinventing Clydefront, looks into the possibilities for a radical renewal of the site by investigating the city’s morphology, and considers that area as an occasion for a wider urban regeneration.

The old port on the Clyde is one of the biggest and most interesting ‘derelict’ areas of the city, a combination of impressive cultural buildings and wasteland at the heart of the metropolitan area; a ‘particular internal periphery’, as my supervisor professor Renato Bocchi wrote.

A Historic Relationship

The Clyde had a key role in the city’s foundation and development, as much as the city’s activities led to the river’s transformation.

The history of the city can actually be read through the changes of the Clydefront: after passing from a non‐navigable wetland to the articulated commercial and industrial infrastructure of the Second City of the Empire, the port was progressively abandoned from the 1960s and infilled during the 1980s.

During the last three decades, the docklands site hosted some of the most important interventions that brought Glasgow from a decadent city that had lost its identity to its present character as a city of culture.

Starting with the SECC, which settled there in 1985, and the Garden Festival event of 1988, and going through to the recent construction of the Riverside Museum and the Hydro Arena, this area has become a prominent tertiary and cultural hub at a national scale. It has attracted some of the city’s most iconic buildings as well as a number of primary business headquarters, for example BBC Scotland’s headquarters.

Starting with the SECC, which settled there in 1985, and the Garden Festival event of 1988, and going through to the recent construction of the Riverside Museum and the Hydro Arena, this area has become a prominent tertiary and cultural hub at a national scale. It has attracted some of the city’s most iconic buildings as well as a number of primary business headquarters, for example BBC Scotland’s headquarters.

Missed Opportunities?

Besides this success, the ex-harbour development was run without a general plan for the area, therefore failing to provide an accessible and enjoyable urban public space. The land ‘in between’ the enormous architectural‐scale sculptures that lie on the quays is a sort of huge empty space, partially filled with the overwhelming presence of car parks and roads.

The goal of combining major cultural and business facilities with urban regeneration cannot ignore the treatment of those facilities’ surroundings and context, and their accessibility from the city’s neighbourhoods.

Clyde Waterfront has a number of notable cultural venues such as the Riverside Museum & Glasgow Science Centre

It can be interesting to compare the achievements of the Glaswegian riverfront hub with the very famous and successful example of Bilbao and its Guggenheim Museum, without forgetting the gap of scale between these two interventions. Even though both areas were former industrial docks, one substantial difference between them is their position in regard to their cities’ cultural amenities.

The Guggenheim area is closely related to the city centre and its cultural quarters, while the focus which was put from the 1950s on the chosen Central Business Area in Glasgow cut the rest of the 19th century centre from what was developed as the ‘downtown’.

The accessibility to the two sites is strongly affected by their location, and also by the different care given to pedestrian links and public open spaces. Besides this, one main issue for the Riverside Museum and the SECC buildings is the presence of the Clydeside Expressway, cutting them off from the neighbouring Victorian west end quarters and amenities. The relationship with the river has also been developed as a key point by Gehry’s design, while it was left unspoken by many of the Scottish buildings, as much as it happened for their infrastructural and geographical context.

From a strictly architectural point of view, while the interesting basement and groundwork of Bilbao’s museum allowed its connection with its context and city, most of the Glaswegian objects completely lacked that attention. Some of them do, however, share a comparable iconic power, presenting strong and distinctive landmarks.

Radical Ideas, Disconnected Reality

An analysis of the city as a whole is surely necessary to investigate the relations between the Clydefront and the metropolitan area, as much as its importance as a regeneration opportunity.

Glasgow can be described as a mosaic of very different urban landscapes, and this makes it an interesting – and at times surprising – case study to be explored and discovered. This number of ‘cities within the city’, often independent or even completely disconnected between each other, were produced by the ever‐changing attitude that is maybe the only permanent feature of Glasgow.

The metropolis’s forming process was characterised by continuous substantial transformations often accompanied by large scale demolitions and bold experimentation with a wide range of urban and architectural ideologies. Following the quarters built during the Victorian era’s thriving economic growth, the 20th century overspill policies, and the heavy renewal of the post‐war Comprehensive Development Areas (CDAs – where ‘comprehensive’ meant complete destruction of those existing city parts before their re‐development), those iconic landmarks seem to embody a new kind of architecture that the city produces in the most radical way.

The old port site has many features in common with a lot of the areas that went through the 1960s and 1970s CDA programme, as it looks like a big void containing isolated objects with no link with their surroundings.

Bridging Cultural Potential

Nonetheless, the waterfront’s position and the importance of its cultural and tertiary hub give it a unique potential. The dimensions of the area and its complexity suggest that a simple urban infill policy wouldn’t be the right way to give it a structure and solve issues of accessibility and lack of enjoyable public space.

What was lost after the abandonment and demolition of the port was indeed an impressive part of the city’s unique character, but it also represented Glasgow’s economic strength as well as a significant part of the city’s history. My research investigated the site through a series of propositions, testing which kinds of landscapes could possibly interact with the context and the site’s existing elements. The proposed strategy tries to build up a ‘system of relations’ for the area, one that considers the city as a whole and allows a new way of walking through its mosaic of atmospheres.

In this sense, ‘bridging’ this strong cultural hub and the surrounding quarters becomes interesting, by means of making it accessible from them and allowing their regeneration. An important link is also proposed with the city’s parks – its most important public spaces – which could become interrelated thanks to the extension of the walkways along the Kelvin and the Clyde. A direct consequence would be the connection between the Clydefront museums and the nearby Victorian cultural hub which sits around Kelvingrove Park, and eventually also the colourful zone of Byres Road and the Botanic Gardens.

Nicola published his research within the ‘Re-Cycle Italy’ programme

The research focuses on the importance of designing with a concern about shaping the urban realm and the context, and of an architecture made of relations and not just of soloist magniloquence. For this reason, the proposed strategy starts from the morphology of the city at an urban scale, and reinvents this area with new spatial principles that interrelate existing and new elements.

For instance, the Riverside Museum, now almost inaccessible and completely isolated, would become a key point for the link between the new public spaces, the old ones and the intermodal connection of Partick Station. Stronger connections between the hub and the old centre of Govan could also be part of a refocused regeneration dynamic, while the restoration of the fascinating docks that sit on the southern side of the river could provide an extraordinary example of industrial archaeology inside a new park of culture.

A summary of Nicola’s ‘Reinventing Clydefront’ research appears in the publication Morphological Studies for Recycling the City, Two Case-Studies of Glasgow and Mira (see p64-68 for the English translation). The thesis was published as part of the Re-Cycle Italy national research programme.